Return Journey

Shelagh McDonald made two albums that were jewels of early 1970s folk rock – and then apparently vanished off the face of the earth. Ian Anderson was ever so pleased to report that she was now back among us.

From fRoots 353/4 – November 2012

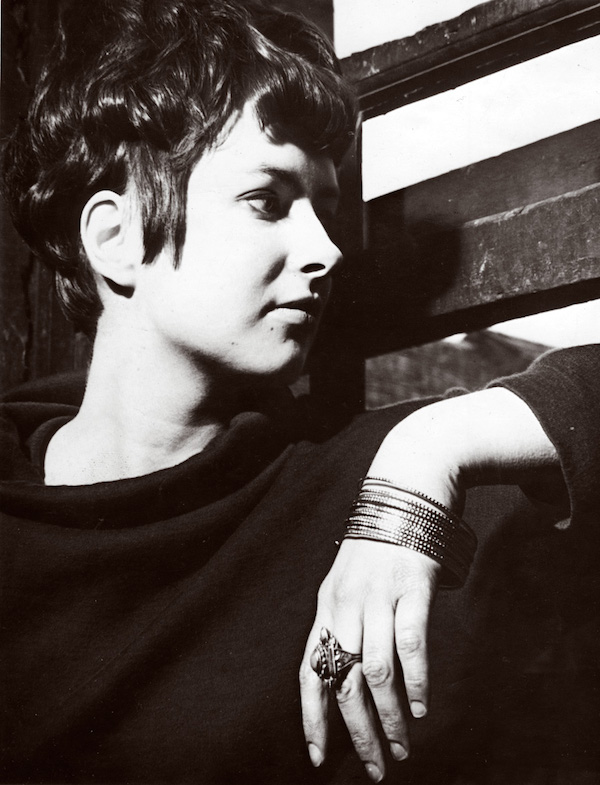

As cult figures go, few come with greater credentials than Shelagh McDonald. A wonderful singer, guitarist and songwriter, beautiful and with a lovely personality, her two LPs (Album from 1971 and Stargazer from 1972) shared musicians, arranger and photographer with her friends Sandy Denny and Nick Drake and were among the jewels of the early ’70s folk rock era.

And then she completely and comprehensively vanished for 33 years, as if off the planet. Vashti Bunyan famously went off in a horse-drawn caravan as part of the legend that aided her old vinyl’s price-inflation. That, it turned out when Shelagh momentarily put her head above the parapet in 2005, was relative luxury compared to McDonald who had been roughing it in tents in the wilds of Scotland for years at a stretch.

But now Shelagh McDonald is back among us, cautiously planning live appearances and hoping to record again. Whilst not exactly a fairytale ending – her emergence blinking into the second decade of the 21st Century was partly brought about by the death of her long-time partner earlier this year – it’s fabulous news for all the fans who have independently discovered her music down the years, and especially those of us who had lost track of a friend.

Now living in Lanark, somewhat startled to find herself owner of a mobile phone and, with the help of her local library, paddling out onto the waters of email and the internet, she’d made contact with old friend Maggie Holland in Edinburgh. Messages and phone calls soon flew thick and fast and in July she came down to revisit old haunts in Bristol, where she’d lived at the turn of the 1970s in the heyday of the Bristol Troubadour club.

“When I was about 15 my parents bought me a guitar. I probably saw Peter, Paul & Mary on TV. Then I heard Joan Baez and wanted to be like that; then I listened to people like Isla Cameron and Dorris Henderson. And then I heard Bert Jansch – first album, Needle Of Death – and I thought ‘I wonder if I could do that?’ I played Anji over and over and over, to get every note.”

That was unusual for a girl back then.

“Yes, back then. You were expected to just strum and look pretty. Pretty boring…”

What were her first steps into playing live, I wondered? “Like many people on the Scottish folk scene at the time it was through Danny Kyle. He ran this folk club in Paisley and that’s where Billy Connolly and all sorts of people cut their teeth. And Josh McRae was around. This is where my parents put their feet down because Josh said ‘Why don’t you come round to my flat?’ So I said to my parents ‘I’m just going round to Josh McRae’s flat to look at his etchings’ –

“When Josh moved over to Kirkcaldy, Hamish Imlach took over. Hamish helped all sorts of people, he was a marvellous man. At that time it was myself and somebody called Ian McGeachy – who later became John Martyn. I loved all the Scottish folk singers of that time – Archie Fisher, Matt McGinn, Josh – they were really nice.”

“So I started going out and doing floor spots. There were masses of folk clubs in the west of Scotland. I got the impression that you could make a living just in Scotland. Glasgow Folk Centre was reckoned to be the best club – up a rickety staircase with naked red light bulbs, bits of newspaper on the walls juxtaposed at exotic angles with the newly-appeared colour supplements, a bit like a speakeasy. There were very few female folk singers around then so I’d get lots of floor spots there for variety.”

“I was doing a gig up in Oban and I met a classical guitarist who later became a flatmate, Katie Stuckey – and she asked if I wanted to come down to London. This was 1967. So while I was down in London I was walking in Chelsea one day, and this big red bus stops and out steps John Martyn in his blue denim jacket and blue jeans and his curly hair, looking like a cherub. So we ran towards each other, sort of mock Wuthering Heights thing in the King’s Road, and he said ‘I’m going down to see my agent, why don’t you come along?’ So that was how I met Sandy Glennon. He couldn’t take me on at that time because he had Sandy Denny and he’d decided to not have too many female artists at one go. But he said ‘If anything changes I’ll be on the phone.’ The day she joined the Strawbs he called me up.”

Shelagh stayed with Sandy Glennon’s agency for quite a while, building up a reputation doing folk club gigs and making her recording debut on a BBC compilation called Dungeon Folk.

“I was pretty crazy about Keith. I met him when we did a gig at Bristol University, and then I think he sent me a card and said ‘come down’. And then [Bristol Troubadour manager] Tim Hodgson said he had a flat so I moved down there.”

“Sandy Roberton came and saw me do a gig – I probably did things like Caruso, Mirage or Ophelia’s Song that I did on the first album – and he pretty much said ‘Do you want to make a record?’ I made him wait for a couple of days to be sure we were both happy with it, which was the intelligent way to go forward … I was aware that Keith had invited him along with that in mind and I didn’t want him to have that revelation at 8.30 the following morning – ‘What have I done?!’”

On her two albums, Shelagh shared musicians from Fotheringay and Mighty Baby who also worked with Sandy Denny, plus Richard Thompson, Danny Thompson, Dave Mattacks, Keith Christmas, jazz pianist Keith Tippett, pedal steel guitarist Gordon Huntley, flautist Ray Warleigh and vibes player Tristan Fry. In common with the Nick Drake albums she had engineer John Wood, photographer Keith Morris and arranger Robert Kirby.

“The first album was terrifying! We didn’t do that many takes and I’d never practised with a full electric band. It was a bit like somebody handing you the keys to a Phantom jet and saying ‘Hop in, see you…!’ We’d go in at lunchtime and we’d be there ‘til about two o’clock in the morning, maybe a quick half-hour break, packing in as much as you could do. It’s quite trying on the voice – if you hear some of my out-takes, my vocals are quite crap: you’re saving your voice for a gig the next day. Nowadays I’m sure a voice coach would tell you a more effective way of saving your voice. The first album, it took me a while to get used to it, but by the second album I was getting more confident. And John Wood was terrific.”

“On the first album I also did two of Keith’s songs, an Andy Roberts, Let No Man Steal Your Thyme, and one of Gerry Rafferty’s – you’ll notice one bit where I la-la-la part of it because I got the lyrics from Gerry at a party. We were sitting on the floor and I asked if I could do that song. So I wrote it down on a piece of paper and either he was drunk or I was, but I didn’t get it all.”

“But the second record was all my own except The Dowie Dens Of Yarrow which is traditional – I enjoyed doing that, with Dave Mattacks. But I must say how happy I was with Sandy Roberton as a producer. He was a dream team, he was terrific. He didn’t tell me that he himself had been a performer, but it explains to me now why he was very sympatico.”

“I used to see Sandy [Denny] occasionally. Sandy loved to be with people, she was addicted to it, but I could tell that she wanted to get down to doing her songs as well. There was this wealth of songs in her, but she couldn’t organise her time – I felt that a lot of her friends should have respected that and given her more space. Which I did, I didn’t want to prevent anything of that flowering.”

Drake was to deteriorate and take his own life. Denny had a tragic fatal accident. Shelagh simply disappeared, as the result of a bad LSD experience that she now doesn’t want to talk about.

When she briefly spoke to the Scottish Daily Mail’s Grace Macaskill in November 2005, she’d said “Everybody was experimenting with drugs, but in April 1972 I took a trip that turned my world upside down. I thought it would be out of my system within twelve hours, but three weeks later I was still hallucinating… I was walking around the shops and looking at people who had no eyes or features, their faces were just blank. It went on for so long, I just forgot to eat and was just skin and bone. I was all over the place and didn’t seem to know what I was doing or where to turn to. Suddenly, I had to get out. My disappearance wasn’t at all conscious. It was a coping mechanism – self-preservation.”

She returned to her parents in Scotland, and was gone. “I didn’t contact anyone. I just disappeared. Because by the time I got home I was very ill. I was aware of lying in bed in my room and the telephone going, and it could well have been for me and my parents saying ‘She can’t come to the phone’. If they did, they didn’t tell me anything.”

“I worked in a bookshop, department stores, all sorts of things. While I was doing these jobs, my brain function meant that when people were speaking – you know when you see things on TV from a satellite connection, there’s a time delay: it was a bit like that. I knew every word that people were saying but it was as if it were a foreign language. By the time I’d made sense of one sentence, they were on another one. By the end of a working day I was worn out trying to make sense of it.”

“I didn’t want to tell my parents as I thought it would worry them, so they said I should go back to college and do some A-levels, sit them again, upgrade some things. I’d get up at half five in the morning, do some study, then go to work, then after work go to the library until it closed. But that was what got my brain functioning again, it took about 18 months.”

Photo courtesy of the Keith Morris Archive

“He gave up the bookshop and we went over to stay on the Isle of Bute. Then we went over to Canada and it didn’t work out there so we came back and thought we’d try over on the East Coast. We ended up living in Wick in the north of Scotland for about five years. Then we were having all sorts of problems with landlords so one day we just got fed up with it and thought ‘Sod it, let’s go and live in tents.’”

“Originally it was only going to be for a few months but it ended up being for six years, though we’d get into a bed & breakfast for Christmas and New Year – the longest we did was 18 months and that was a bad winter. Just a two-man tent, carrying everything on our backs. We were both on benefits: we’d registered for work in the area and thought we’d start off in the tent and then get into a flat and get the jobs but nothing ever meshed together. I’d never been in a tent before in my life, I’d had a cushy middle-class lifestyle, but Gordon had wintered in the Antactic, in tents for eight months. I got better at it…”

In 2005, Sanctuary/Castle re-issued both Shelagh’s albums plus all the available out-takes and the Dungeon Folk tracks on the double CD Let No Man Steal Your Thyme. They’ve subsequently gone under and even this re-issue is now hard to find, but it did catalyse a flurry of ‘Whatever happened to…?’ features in the press.

“The Scottish Daily Mail did an article about me in 2005. Gordon got it. It was a lovely sunny day, we were in the tent. He says ‘Oh this is interesting, this is about a folk singer, somebody’s beaten you to it.’ I’m saying ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘Here, read this.’ So I made lunch and forgot about it, and then ‘Oh, where’s that article?’ So I pick up this newspaper and there’s this big photograph of me and it was surreal – like looking at your own obituary.”

“It said my parents had died. It was something I had been preparing myself for, but it was still a shock. So to find out where my brother was and to say I liked the article, I went to the newspaper and they put me through from the desk: it was Grace Macaskill, lovely girl, good journalist. It was only then that I learned anything about the folk revival, I hadn’t a clue about anything.”

“So then we had another few years to do in the tents until 2008 we got a flat.”

“I haven’t been out and done it in public yet because I’m a perfectionist. Having reached another level it’s demanding more of me as a performer and I haven’t done that for a long time. It’ll be ready when it’s ready. But I can take pressure – putting up a brand new tent on the side of a loch at Fort William, not a breath of wind on a beautiful day and then along comes a hurricane and blows it to the other side of the loch and you’re left standing there with nothing in the worst storm for a hundred years, swearing like a trooper …”

And how does she feel about her old body of work? “At first I couldn’t listen to it, but now I’m pleased, for the age I was. If I was writing it now, I would expect something different, but everything is of its time. I would like to make one other good album. If there were more in the pipeline, that’d be OK but I’d like to do that one, for a sense of completion. What you’re seeing here is only a quarter of me, three quarters of me is with Gordon. I’m enjoying that quarter to the full, and I feel there’s one thing left for me to do.”

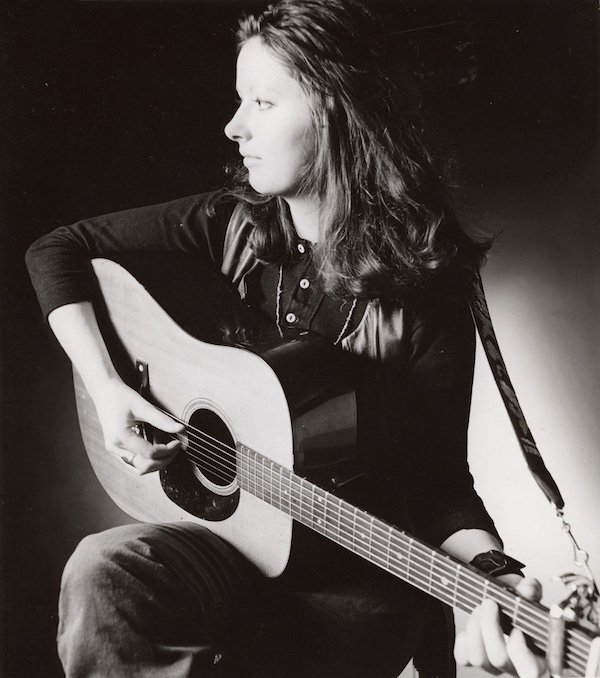

Since the interview took place, Shelagh tells me she’s been slipping out and doing incognito spots at local open mics and folk clubs. She’s doing her first official low key gig in London in January 2013, there has been radio interest and suggestions of projects from admirers in the business.

Welcome back!

FOOTNOTE:

Shelagh briefly returned to live performance – here she was at that London comeback gig in 2013 – and by the summer of that year had completely regained all her skills. She tentatively recorded a new album, but for health and personal reasons has now largely retired again. She’s still living in Lanark.

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)