Pascal Diatta & Sona Mané

Hunting the Balanta guitar man. By Ian Anderson, updated from the feature in Folk Roots magazine issue 70, April 1989.

“If we’re lucky,” our friend Lucy Duran had said just before a West African trip at the end of 1987, “when we go to Ziguinchor we might finally get to hear Pascal Diatta.” As it turned out, the man proved elusive and we never got to meet him on that visit. But a year later, as I was about to head back to West Africa again in order to avoid another unspeakable Christmas period in England, Lucy called me up. “I’ve just had a letter from Mfamady Cissokho’s son in Ziguinchor…” [Mfamady Cissokho is a fine traditional kontingo – small lute – player] “He says that Pascal Diatta is back in Ziguinchor at the moment and I’d find him if I went there soon.” Sadly, with a long trip to Mali for BBC TV in the offing, Lucy wasn’t able to make this visit, but I took the information, packed the microphones and tape machine, and made a definite mental note to hunt the man out. Luck was to be on our side this time.

After a week in the Gambia crammed with formal gigs and informal visits to various traditional musicians we’d met on previous spells in the country, it was time to go and play ‘hunt the guitarist’. All we knew about Pascal Diatta was that he is from the Balanta people who are mostly found in Guinea Bissau and Casamance, southern Senegal. No commercially produced tapes of his were to be found in the numerous local market stalls, but he’s been heard regularly on the local radio stations in Senegal and the Gambia and is spoken of in awed tones. Dembo Konte had seen and heard him play at a wedding ceremony in Brikama some years ago and sang his praises; the problem was, any time Lucy Duran had gone to look for him, he’d been away on his travels.

First, we had a minor hiccup to deal with. Dembo had taken proud possession of a new (well, second-hand) Peugeot 505, transported from Europe out of the proceeds of his recent touring with Kausu Kuyateh, to replace his ancient 504. The mysteries of the latter’s gearbox now required full membership of an arcane society in order to operate it! The problem was, until January 1st the 505 still had Belgian number plates, and on December 24th a government decree had gone out requiring all cars with foreign plates to be taken off the road. After a bizarre and hilarious journey around the back footpaths of Gambia’s Western Division, in and out of bemused people’s compounds to avoid police checkpoints, Dembo eventually got the car and us back home to Brikama, and so had to do some wheeling and dealing with local taxi drivers to get another vehicle and driver to takes us all the 50 mile drive south into Casamance.

The deal successfully concluded, we hit the road early one late December morning. As you drive into Casamance, the landscape changes from the low scrub, red dust and sparsely dotted trees of the Gambia into an altogether more lush scenery. Big silk-cotton, mango and baobab trees surround neat Jola villages with their distinctive compounds, and then as you near the Casamance river it metamorphosises into misty, open stretches of mangrove flats, mysterious spaces in which large wading birds flap lazily around. Finally, you cross the river itself (having been fleeced by the statutory Senegalese police check, ever on the look out for a barely-legal excuse to remove currency from your pockets) and enter the lightly-industrialised major town of this region, Ziguinchor.

Ziguinchor’s broad streets still carry the character of French colonial days in the centre, but just outside of that is a bustling, crowded market area typical of any West African town. We headed for a tiny restaurant, Le Bel Kady which we’d visited a year earlier and we knew had rooms to rent. Rooms are indeed what they rent – four walls, a roof, and a concrete platform with a mattress-sized chunk of foam rubber – but they’re very cheap, adequately clean and provide a satisfactory base. After a quick sortie up the street to the market for essentials – finding the just released new Youssou N’Dour Gaïndé tape that hadn’t yet even reached the Gambia and, for Dembo, a superb half calabash for his next kora resonator – we put our feet up in the cafe while Dembo went to pay respects to old friends and put out feelers for the whereabouts of the man Diatta.

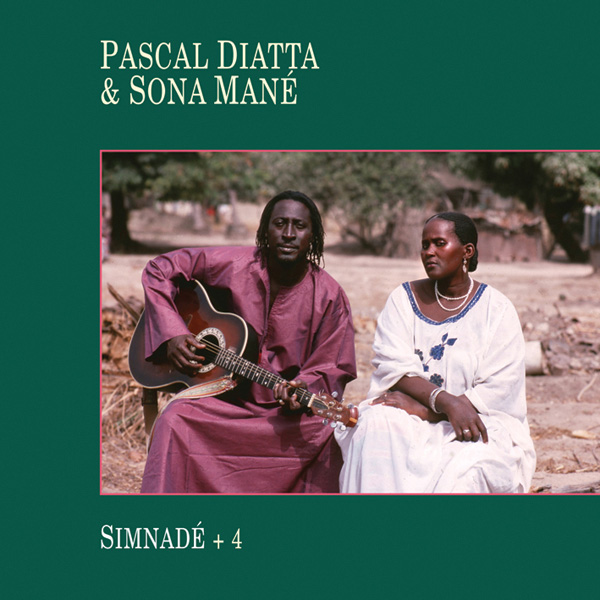

Pascal Diatta & Sona Mané in their compound just outside Ziguinchor, Casamance © 1989 Ian A Anderson.

Half an hour later, with our meal barely finished, Dembo returns with a broad smile and a stranger. His friends hadn’t been at home, so he’d popped into the radio station to ask for clues. By immense fortune, Pascal Diatta had been there at the same time.

You are immediately struck by the man’s presence. He’s an imposing figure with slightly aquiline features and his hair worn in moderate locks. On this occasion, he’s wearing a red beret and shades, to add to the impact. With the help of Dembo and Gaelle Finley, an English-based French woman who’d joined us on this outing, we overcame several language barriers and explained that his reputation had reached as far as England, that we would very much like to hear him play and, if possible, record him with a view to making an eventual album if everything turned out right.

But a snag immediately raised its head. Some years ago, an American woman had come there with a similar request, recorded quite a lot of his repertoire, taken the tapes back to the States and released some of them on a Lyrichord compilation of Senegalese field recordings. A copy of the finished record eventually showed up in the post, but that was the last he’d heard – i.e. no royalties. Trusting Westerners and their promises was therefore, understandably, a problem. Luckily, Dembo was able to give me good references from his own experiences, so we arranged that Pascal would return that evening with his wife, singer Sona Mané, and we’d set up a makeshift recording studio (well, a Pro-Walkman, a pair of mikes and a stand!) in our hotel room. We walked a little way up the road, during which time he was greeted as a celebrity by a number of passers-by, shook hands and he left us, leaving us amazed by the ease with which we’d found this seemingly elusive legend.

Back at Le Bel Kady, our standing and credit rating obviously suddenly improved by the status of our recent visitor, we whiled away a few hours gaining caffeine ODs on too many little glasses of hataiyo tea and watching bad French movies on Senegalese TV. Mind you, the adverts are amazing: there’s one for Maggi seasoning which is exactly the same script as a ‘60s Oxo advert, except that the whole thing is set in a local compound with the men sat glumly around a large enamel bowl of apparently unappetising food, only for the ‘Katie’ figure, one of the wives, to bring smiles to their faces with the Maggi! Sarah Coxson meanwhile discovered the drawbacks of being a vegetarian in Ziguinchor when fish is off the menu; it’s rice and chips tonight!

Later, Pascal returns with the equally striking Sona Mane and, after waiting a while for the sounds of passing traffic, local revellers and the hotel sheep to die down, we set about recording.

Dembo, our driver Bobo, Gaelle, Sarah and myself spread ourselves out on the hotel room beds, and Pascal produced his guitar. Here’s a surprise: it’s an Ovation! (More about that later.) Here’s less of a surprise, since guitar strings are virtually unobtainable in those parts – two of the strings have knots in near the first fret, and the bass one doesn’t look like a conventtional guitar string at all. Do I have a capo to avoid this problem area of the neck? I must have had a premonition, since it had been a last thought as I’d finished packing back home. A quick run through a song – and what a song! – to set levels and position mikes, and away we go.

This is utterly extraordinary music. Pascal plays guitar unlike any West African I’ve ever heard. He’s got a completely unique two finger/thumb picking technique, pulling out fast, staccato notes and flurries of runs and riffs. The only things I can point at to draw any similarities with are quite clearly totally coincidental: at times there are little things which remind me of valiha and marovany from Madagascar, that really fast rural merengue they play on melodeons in the Dominican Republic, and flashes of Dick Gaughan, Joseph Spence and Rev. Gary Davis! Sona Mané sings the lead, pitched much lower than the vocals one is used to hearing from West African women, and Pascal mostly sings harmony; once again, what their harmonies occasionally remind me of must be only coincidence – more like East Africa, Zambia and Madagascar. Maybe a Portuguese colonial connection? Probably not – I expect Alan Lomax and his ‘cantometrics’ theories could have convincingly explained it all…

By the third song, Dioudiou Coumbota, which stretches out to over ten minutes, they’re really cooking. The guitar embellishments get faster and wilder as the song progresses, throwing in unexpected stops and exciting riffing. As they draw to a close on this one, with Dembo lying full length on a bed and making exaggerated hand gestures of praise, everybody forgets that it’s a recording session to burst into applause. Hotel people are gathering outside wanting to come and hear the action. There’s no doubt about it; this music richly deserves to be heard by many people in other parts of the world.

[Completely without influence, Diatta & Mané played as if making a whole album direct to disc, doing their own ‘fades’ at the end of each song, waiting a few seconds and starting the next one. The fades on our eventual album release were merely a slight technical tidying of what they tried to do acoustically. Presumably, they assumed this was how records were made…]

We recorded the best part of 90 minutes of music, and then got down to asking about Pascal’s life. He was brought up in a missionary-run orphanage, and eventually became interested in music. At some point he became passionately hooked on the sound of the guitar, so he decided to build his own. His first attempt was made using part of an oil drum as the body, and with strings made out of un-braided bicycle brake cables (which turned out to be what he’d currently had to replace his broken Ovation 6th with); his second, improvised in similar fashion, was made from a wooden packing case. Eventually, a kind woman at the missionary school had enabled him to buy a proper guitar.

During a spell doing military service in the army, he’d become a considerable athlete, so much so that he’d gained the nickname ‘Keno’ after that great African runner. Keno is also the local name for rosewood (the king of woods), the immensely strong material used for the necks of koras among other things. When he left the army he felt that he had to justify the name by being the best at something else, and so set about becoming the king of guitar players.

He’s very proud of what he’s achieved, stressing that he’s evolved his style without influence from others and is aware of his uniqueness. I asked him about numerous musicians. Most of the famous Senegalese stars like Baaba Maal he’d heard of but not heard; he had no knowledge of Ali Farka Toure or Jean Bosco Mwenda, had never knowingly heard any of the American blues players, and in spite of his appearance had little awareness of reggae which enjoyed a fanatical following amongst young Senegambians. Lucy Duran had suggested to me that his guitar playing was based on Balanta xylophone music but he denied this too, though obviously he’s very familiar with it. He writes all his own songs rather than the widespread practice of elaborating on common traditional stock, and says that he taught Sona Mané her singing style to fit his material. Oh, and I later tried to play his guitar and found that the state of the stringing made it quite impossible – I was then even more impressed by the music he’d been making!

He makes a meagre income from music by playing for wedding ceremonies, circumcisions and other such events, occasionally on the radio and in the nearby rich tourist resort of Cap Skirring, sometimes with a small troupe including percussionists and dancers. It was here that a few years back he was befriended by another American woman who, totally without any prior announcement, sent him the Ovation guitar and case on her return home. That’s the kind of reaction his playing inspires.

The tapes we made on that awe-inspiring night were edited and released in Britain as the Rogue Records LP and tape Simnadé (Listen!) in 1989, later expanded with four more tracks for CD release in 1992. [All are long out of print in physical form, but now available again as a digital download – https://ghostsfromthebasement.bandcamp.com/album/simnad-4 ]

There were plans to bring them to the UK for the 1988 Bracknell Folk & Roots Festival and a short UK tour but Pascal vanished on his travels again right at the crucial pint for visa and work permit applications, so it never happened. Later, it became apparent that the decent amount of royalties for the album which we sent down to Pascal via a trusted Gambian intermediary were apparently intercepted by a relative and never reached him – which makes you wonder about the tale we heard surrounding the earlier American release. Without any possibility of visiting Ziguinchor again, all my subsequent attempts to contact him failed.

Footnotes: In 2018, Matthew Lavoie’s The Wealth Of The Wise blog reported that Pascal and Sona performed together until their divorce in the late 1990s. Pascal remarried and continued to perform with his second wife, until passing away in 2017. In 2003, Sona was recruited by the group Njama Naaba and continues to perform regularly with them. http://thewealthofthewise.blogspot.com/2018/08/pascal-keno-diatta-sona-mane-balanta.html

Here’s what some of the contemporary reviews of Simnadé said:

“Mané’s passionate, husky voice stuns and enchants, sending shivers down the spine. But it is Diatta’s amazing finger-picking stop/start guitar that really takes the breath away, providing looping and spiralling patterns over and under the swooping and soaring voices. This is utterly extraordinary music.” (**** Q Magazine review).

“Inspiring, earthy African acoustic folk with criss-crossing vocals and harmonies over Diatta’s flowing, weaving flurry of notes.” (Music Week)

“Simnadé is a stunning debut album. Pascal Diatta’s unique guitar playing provides a constant flurry of riffs, runs and notes as the driving background to the pair’s startling vocals. It seems amazing that people of such ability and originality, with real power to move audiences from any culture, have gone unrecorded for so long.” (The Catalogue)

“Jackpot! The chance to hear this record was an incredible joy. He sounds like a strange blend of Ry Cooder, merengue and too-fast ragtime picking. The close harmony of the voices tied tightly to the guitar lines make for a striking and different sounding music.” (CMJ New Music Report)

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)