Matchbox Days

Really! The English Country Blues 1967-69

(Sleeve notes for Matchbox Days, Ace/Big Beat CDWIKD 168, 1997)

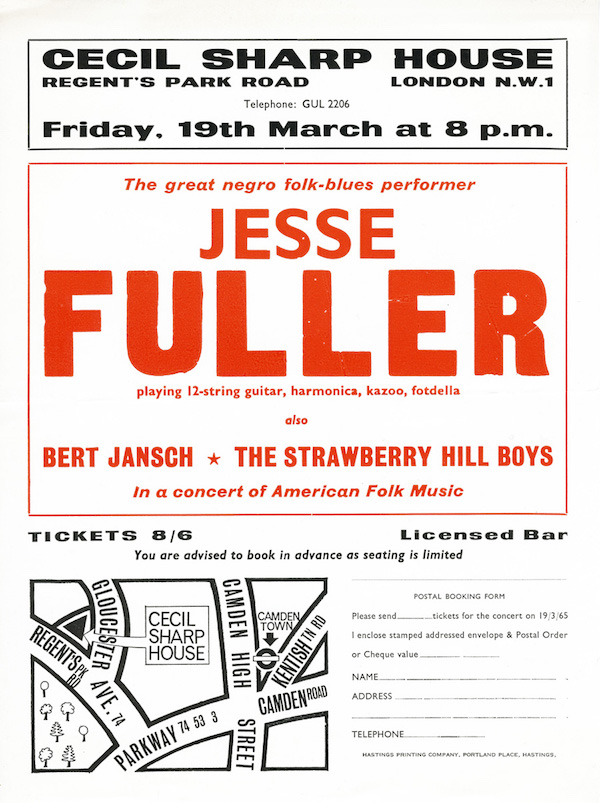

Although most of the written history of the British blues boom of the mid-to-late 1960s centres on the electric bands who were later to mutate into progressive rock and heavy metallurgy, when it peaked in 1967 to ’69 there was strong acoustic blues scene in this country as well. Many of the artists who suddenly found themselves the centre of much attention from the media had come up at least partly through the folk club scene. Overnight, they found themselves playing the same circuit as the major blues bands.

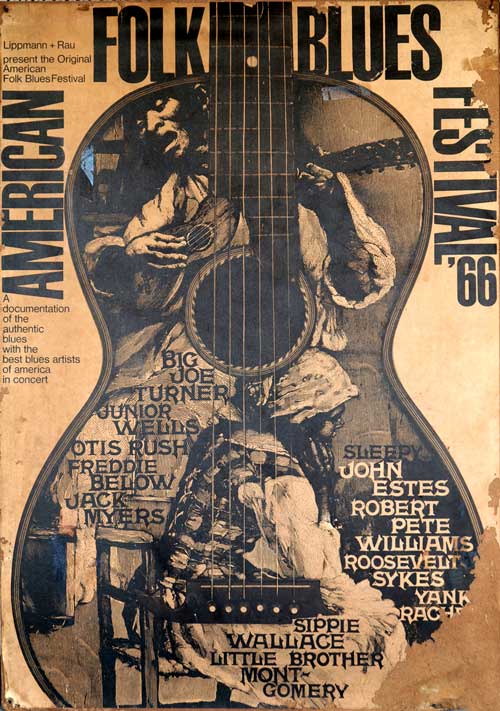

Those were interesting times indeed, but the beginnings of it go much further back, possibly as far as recorded blues music has been available in this country. English traditional singer Bob Copper vividly remembers buying 78 rpm records by country blues singers like Sleepy John Estes in the mid 1930s, and the white blues of Jimmie Rodgers was widely popular here. I can’t believe that there weren’t British musicians who felt inspired to learn the songs off those records.

Wizz Jones

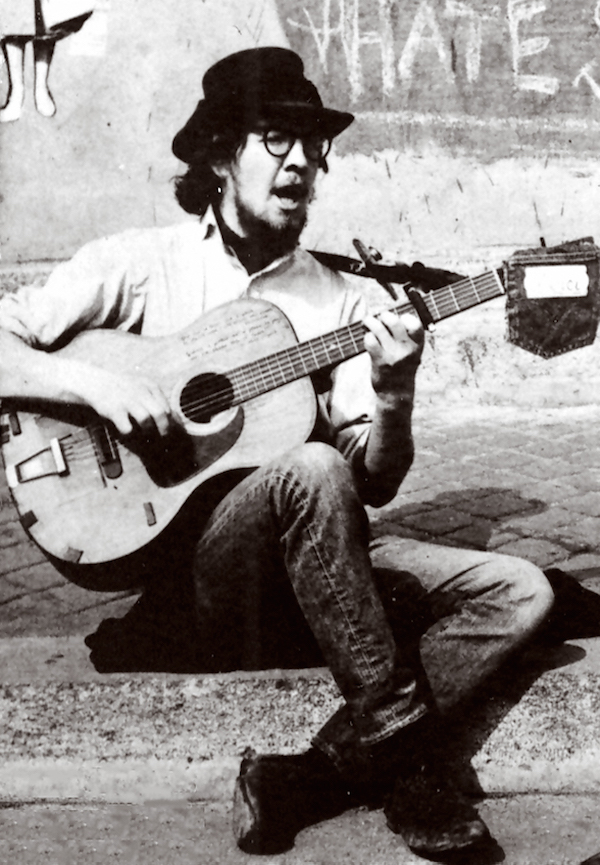

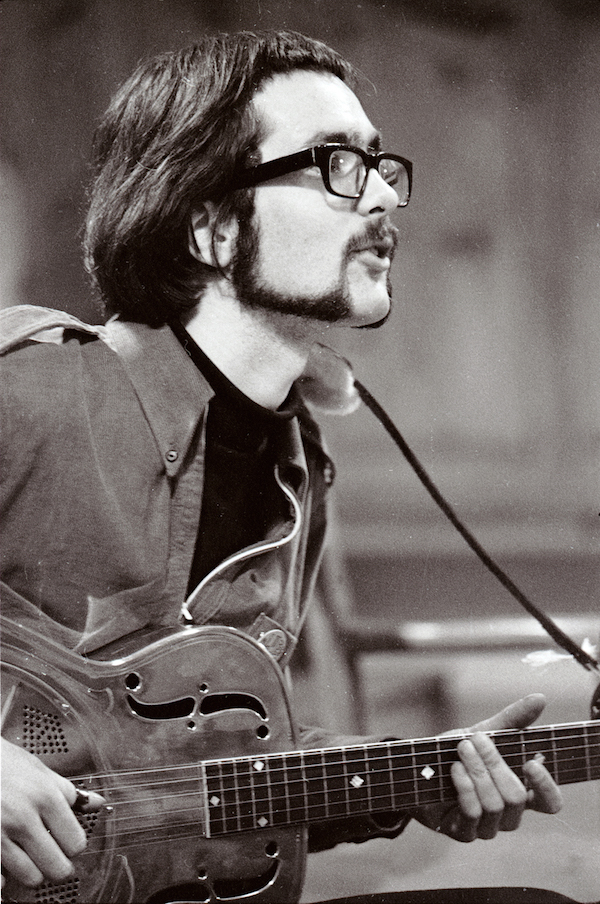

Sitting at the feet of those first visiting Americans and the British musicians like Alexis and Cyril Davies who were already up on stage were a handful of guitarists who would affect the whole course of guitar playing on the British folk scene. Chief among these were Davy Graham and Wizz Jones, who would later add other non-blues influences, large pinches of total originality, and inspire legions of subsequent players from Bert Jansch and John Renbourn onwards. English folk guitar colossus Martin Carthy readily admits that his legendary thumb work still bears the mark of styles that evolved in the days when Big Bill Broonzy was the No. 1. instrumental hero. Thus, blues became a major ingredient in the folk club repertoire throughout the 1960s.

Dave Kelly

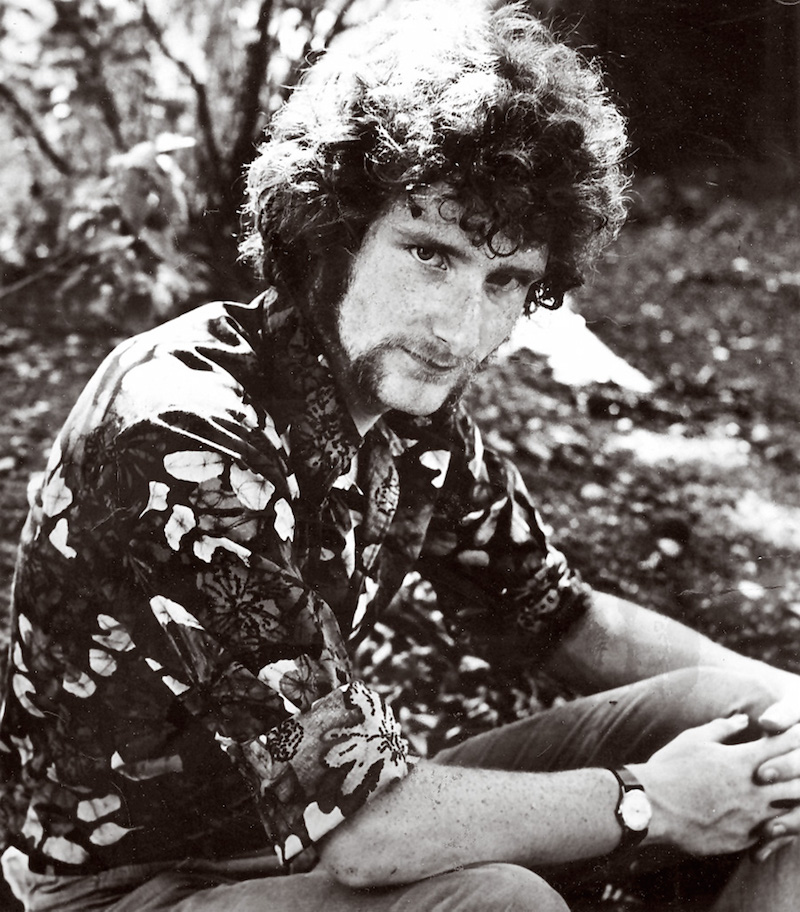

Ian Anderson

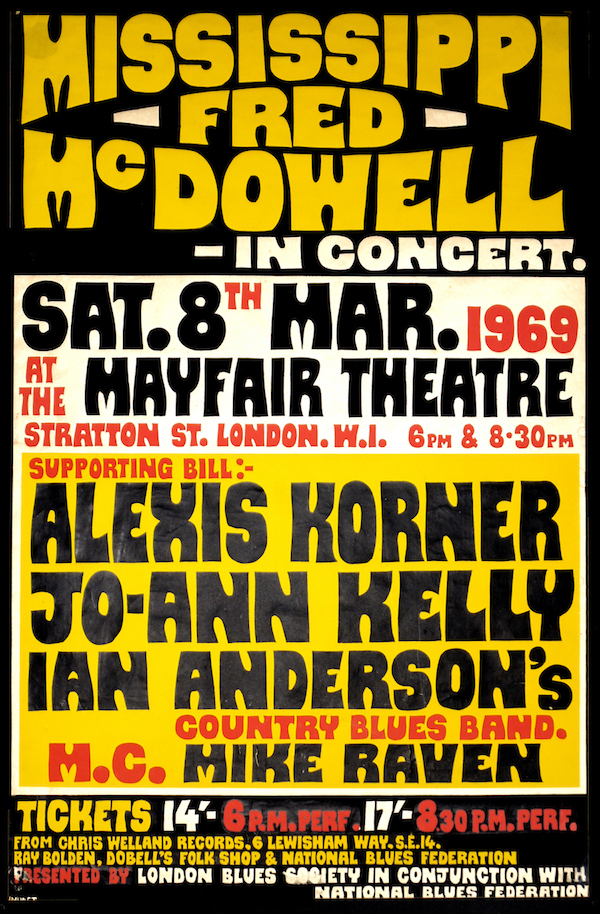

All of a sudden, the kind of blues you heard from Broonzy, McGhee and White seemed rather slick and fell somewhat out of fashion. People began hacking necks off wine bottles, hunting for National steel guitars and singing in very Mississippi accents. When you’d read Paul Oliver’s book Blues Fell This Morning and Sam Charters’ The Country Blues, bought the Robert Johnson album and just seen Fred McDowell, it didn’t seem at all preposterous to feel that you could change overnight from an 18 year old English person into an elderly black Mississippi sharecropper. All around you were people doing it with ease!

Back in those days, blues players were a regular feature of many folk clubs. You fairly quickly learned what was acceptable (just once in 1966 I hauled an electric guitar, an amplifier and a bass guitarist into a Bristol folk club to do a bit of pretending to be Muddy Waters – just once!). One occasionally met other local folk blues guitarists – a popular one in Bristol was Al Jones, for example – but the inkling to us Bristolians that they might be more widespread first came in 1966 when Mike Cooper from Reading turned up to do a floor spot, National steel guitar glinting in the candle light. He told us about some other players he’d recently met from South London, so early in 1967 the widening circle of bluesers in Bristol persuaded the owner of the Bristol Troubadour (a six-nights-a-week folk music coffee house) to let us hold monthly blues nights, booking Cooper for the first of them. This became Britain’s first ever specialist country blues club.

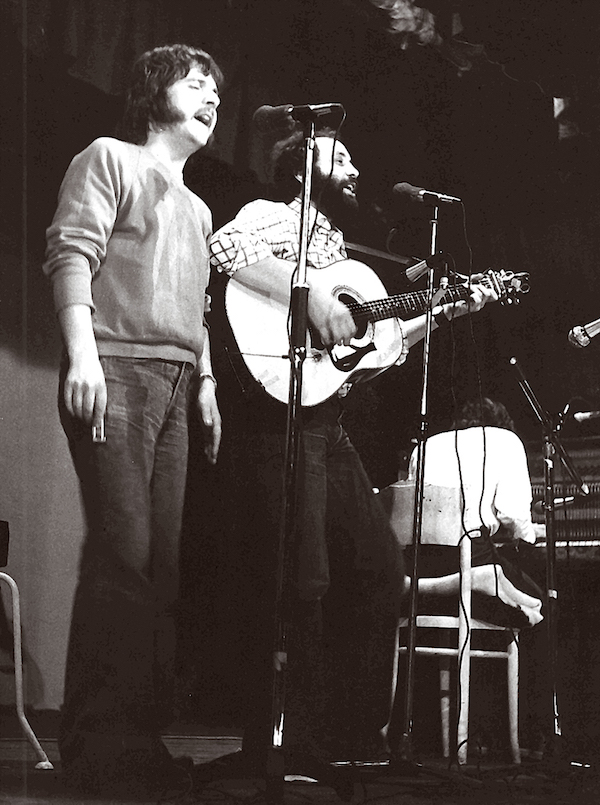

Jo Ann Kelly

After that, the Troubadour was too small. We moved the club, by then called Folk Blues Bristol And West, down to a city centre pub; within a year we were in a room that held 250 and was regularly packed with a queue around the block. Blues became big business in Bristol – the top local electric band, The Deep, eventually providing musicians for the John Dummer Band, the Groundhogs and my own later trio. Our first guest in our new premises was Dave Kelly’s big sister, the late and much-missed Jo Ann Kelly. In those days, audiences were used to female singers being Joan Baez clones, and this small blonde girl in spectacles didn’t look awfully like a blues person. She unpacked her frightfully cheap-looking guitar from a soft case, sat down, and immediately became an unholy mating between Memphis Minnie and Charley Patton as she piled through Moon Going Down and Nothing In Rambling. Hey, not even blokes could do Charley Patton that well (this was 1967, remember, and men were not so liberated). In Bristol, a star was born …

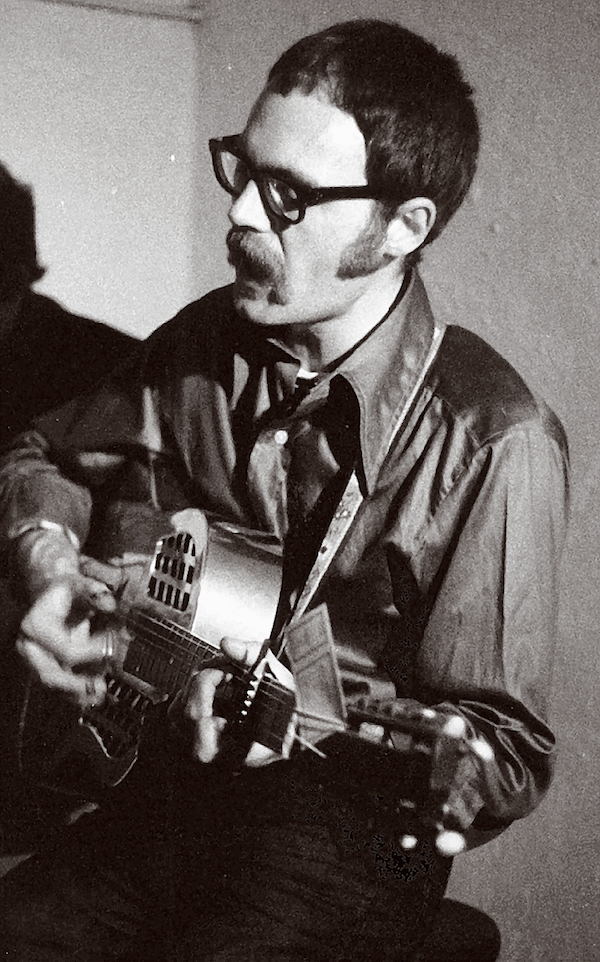

Mike Cooper

I think Mike Cooper was already a full-time musician when I first met him. By the summer of 1967, so was I – there were too many late night homecomings from gigs to make doing a proper job seem any sense at all. As we travelled around the country, we discovered other localised blues scenes where there were really excellent cells of players who had followed the same course, inspired by those scratchy old blues re-issues. From Brighton to Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester, round in South Wales and especially in Leeds and South Shields, there were strong country blues scenes apparently just waiting to find out about others elsewhere with a like mind.

The Panama Limited Jug Band

t the beginning of 1968, as all the main singers were regularly appearing in the Bristol club, Mike Cooper and I took an idea to Gef Lucena of the local record label, Saydisc. We’d both made limited edition EPs through him which had sold out quickly, so we proposed starting a blues label which got called Matchbox. Over the next few months, both of the Kellys, Cooper, myself, Prager & Rye, the Panama Limited and Missouri Compromise went out to an echoing Quaker Meeting House on the outskirts of Bristol at Frenchay. Gef set up his ancient mono Ferrograph and we huddled around the microphone and an old iron stove, recording tracks.

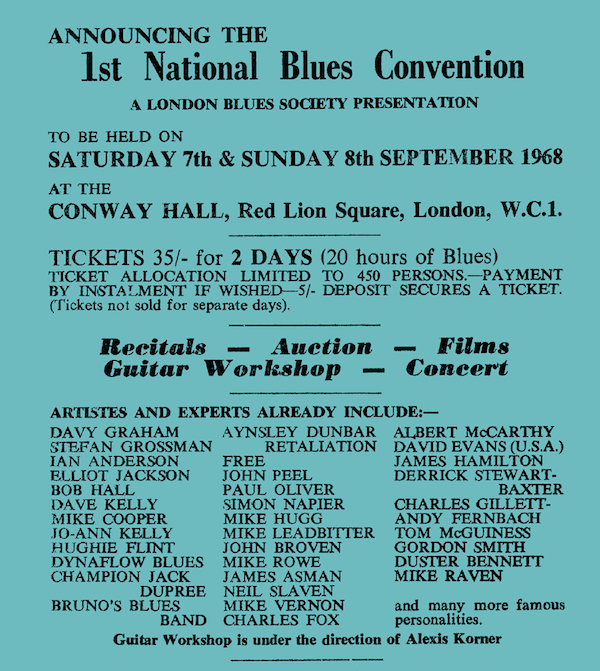

The time was just right. In March ’68, Alexis Korner wrote a major piece about British blues in Melody Maker where he mentioned us acoustic players alongside the electric bands who were already achieving vast cult followings. Mike Raven was playing tracks off the EPs on his Radio 1 blues show. When the first Matchbox LP, Blues Like Showers Of Rain, appeared in July ’68 – it was such a shoe-string operation that Gef had to hand-stick the first couple of hundred sets of labels to get it out at all – everything went silly. John Peel, then as now the first to spot something good happening at the roots, played it every night and had most of the artists guesting. Melody Maker went to town on it, followed by the rest of the music press and even national newspapers.

Jerry Gilbert put on the first major British country blues festival at Farnham in Surrey. In September, the first of two National Blues Conventions was held in London and people from all over the country – players, collectors, enthusiasts and heavyweight purists – got to meet each other and enthuse or come to blows. Major record companies descended in swarms, datesheets filled solid. National steel guitars became the ultimate status symbol of the year, and very expensive – early birds like Cooper and myself counted ourselves as rather lucky to have found our first ones for under a fiver each when nobody wanted them at all.

Liberty Records jumped in with a second anthology titled Me And The Devil, produced by the Groundhogs’ Tony McPhee. I formed a trio called, after a piece of stunning inspiration by Al Stewart, Ian Anderson’s Country Blues Band, moved to London and recorded an album called Stereo Death Breakdown which also came out on Liberty.

Steve Rye, Simon Prager

But back to ’68. At the end of the year, a motley collection of enthusiasts which included Alexis Korner, Radio DJ Mike Raven, Ron Watts (later to be the first promoter to regularly book the Sex Pistols, but that’s another story…) and myself formed a short-lived organisation called the National Blues Federation, initially out of the Notting Hill flat which Ron and I shared (to the consternation of our neighbours). It didn’t last long, but I think its finest achievement was the club and concert tour we set up for Fred McDowell from the payphone in the hall. With roadie Gareth Hedges, he spent a month on a triumphant circuit of Britain, playing to packed houses and getting mobbed everywhere he went. Having him as our house guest during that tour and being lucky enough to support him with my trio on many of his dates still remains one of my most treasured experiences in music. A wonderful man.

After that, it seemed to wane as rapidly as it had come. But things never really dropped away entirely. A whole generation had a bit of blues injected into their bloodstream, and racks full of records by the American originals have stayed visible ever since. Whilst some of us went off to explore other musical territories, others stayed working away at blues music – people like Dave Kelly, Dave Peabody, Steve Phillips, Brendan Croker and others now having decades of experience to draw on.

Al Jones

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)