Gitara Gasy

Ian Anderson started out to write a short feature on a couple of guitarists from Madagascar, D’Gary and Haja. But one thing led to another …

From fRoots 178, April 1998

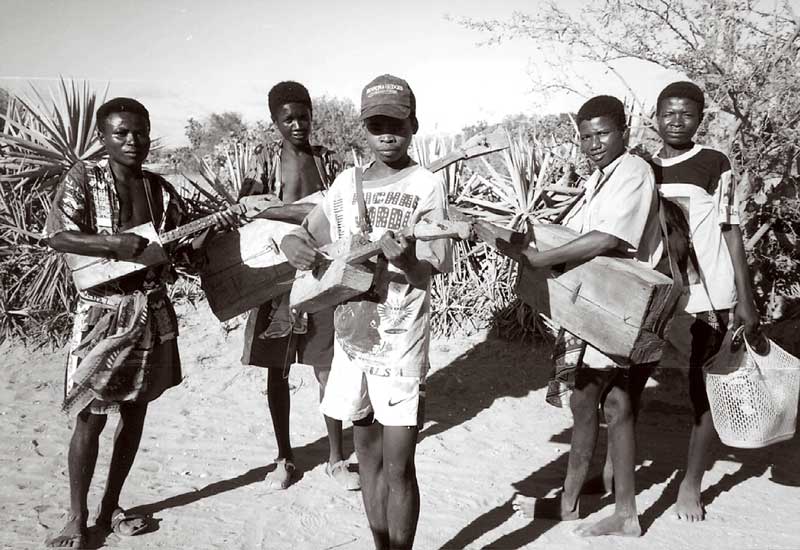

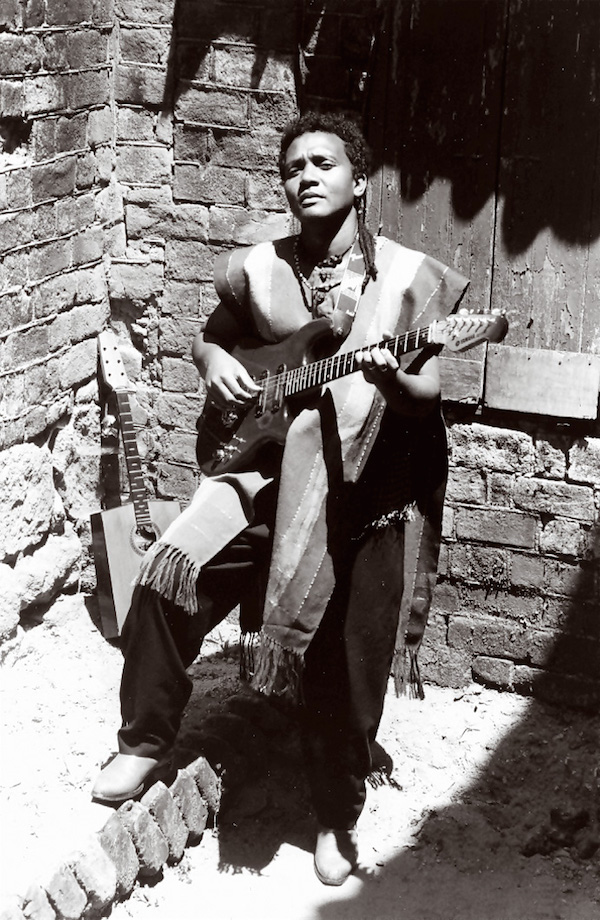

Kabosy players. Photo: Ian Anderson.

Back where you were, it was Boxing Day and you were maybe slumped, turkey-stuffed, in front of the TV, or perhaps stumbling back from watching some dodgy Morris side down the local. Meanwhile, some 30 km outside of Tuléar in south west Madagascar, it was 32 degrees of dry summer heat and we were bumping dust-caked along a sandy coast road bounded by baobabs, giant sizal and acres of impressively spiky cactus.

Calling a roadside halt to get in the mango supplies – 50p for a shopping basket full, including the basket – we realise something’s going on in the village where we’ve stopped. Crowds of dancing people are legging it up the road, and women are already in toka (local rum) fuelled trance. Half a dozen wandering groups of kabosy players (the small Malagasy box guitars, probably descended from the Arabic lute and locally called mandoliny, curiously fretted and some actually of improbably large size) are sauntering in from the bush. A protesting zébu is being hauled off to meet its maker, ceremonial fish tied around its neck, and then from over the brow of the hill comes the unmistakeable sound of an electric guitar cranked to 11.

By luck, we’ve hit this village on the one day in every seven years when they hold the sambatra circumcision ceremony and an all-night party is about to commence. Under the village shade-tree, the festivities are led by Orchestre Rivo-Doza (‘the cyclone band’), comprising one probably Russian-made lead guitar, one 3-string bass guitar and a partly home-made drum kit. The fearsome music they’re driving out is called tsapika.

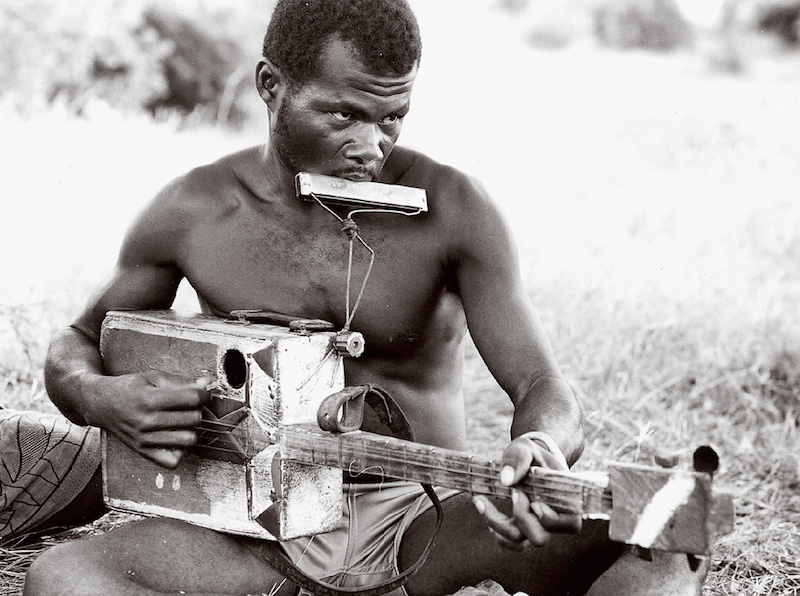

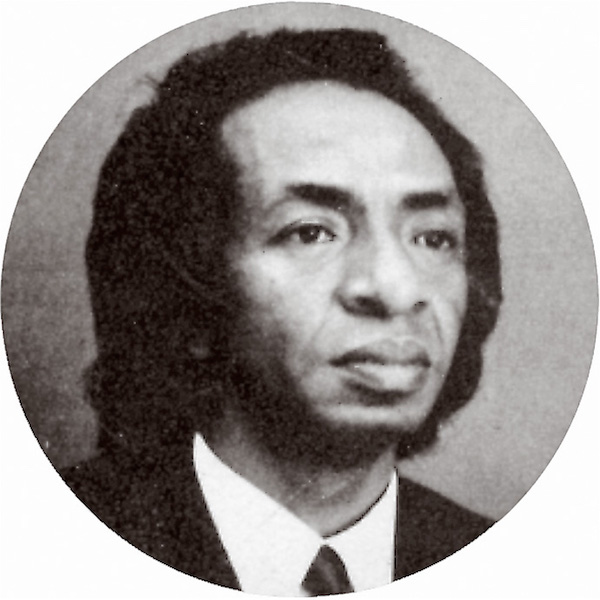

Torosoa. Photo: Ian Anderson.

No sooner do you think you’ve figured out something about Malagasy guitar than the bigger picture expands faster than you can follow. The more you visit, the more music you hear and musicians you meet, the less you realise you know. I’m married into this culture, been there often, and it’s still bewildering. I’d intended to interview a few current players of apparently marovany-influenced guitar, but the project spun off into a maze of byways. Instead of a simple feature, this is a scratch on the surface, a whiff of the scent, barely a beginning. Just like Madagascar’s fertile soil produces the most intensely flavoured fruit – pineapples that are pineapply beyond your taste-buds’ wildest imagination – this musical culture is serious.

Of course, grinding poverty and the desire to get out of it breeds a certain desperation, not the least among some Malagasy musicians who walk around with an accumulation of each others’ metaphorical knives bristling between their shoulder blades. Then there are subtle inter-tribal rivalries. You learn the hard way to beware of the hidden agenda, and take some assertions with a large pinch of salt. It’s so easy for us vazaha (foreigners) to make big errors of assumption, and then have people tell us what they think we’d like to hear …

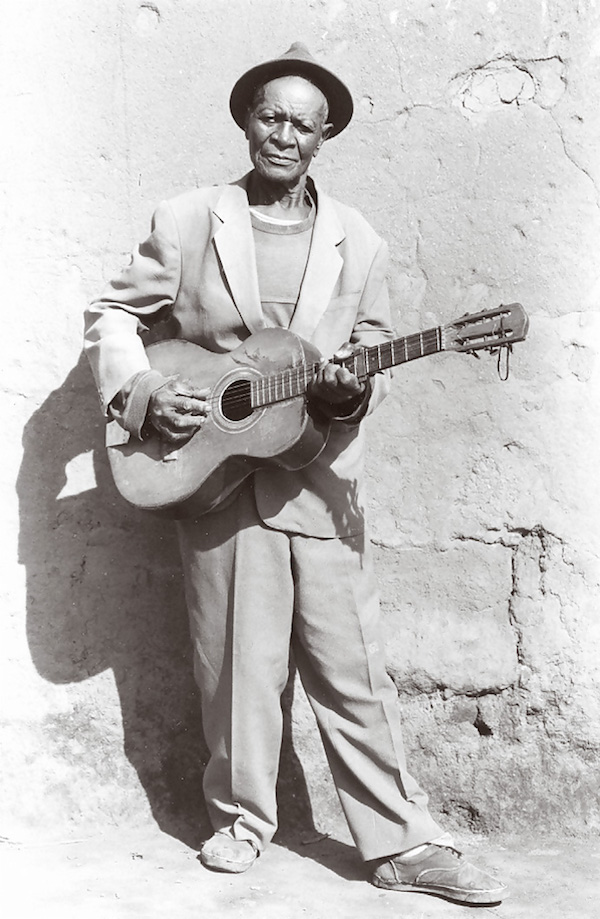

A member of the Orchestre Rivo-Doza. Photo: Ian Anderson.

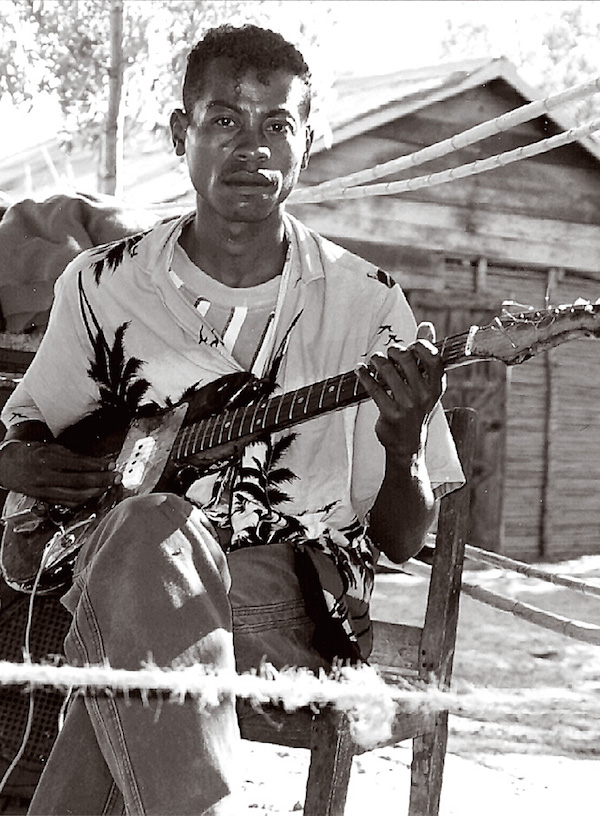

Sambiasy & Manantsoa. Photo: Ian Anderson

Long before Ny Antsaly, Madagascar’s first internationally acclaimed touring group, were playing for the crowned heads of Europe (and the Welsh National Eistedfodd in 1962), [PHOTO] the guitar was already a central instrument alongside the valiha (tubular zither). A big Malagasy export in the ’60s were the pop group Les Surfs, hit makers in France with Francophone covers of Beatles and Motown tracks. The major local ’70s band Mahaleo, whose excellent guitarist/ songwriter leader Dama still performs and records when not busy as a politician, took as much influence from international soft rock of the Simon & Garfunkel/ Eagles era as they did from local roots. Their great success was in finding the perfect blend, taken up by later bands like Lolo Sy Ny Tariny. Jazz, rock, reggae, rap – all those international musical forms have their local practitioners.

Ny Antsaly

My brother-in-law Naina suggested that a visit to his old guitar teacher might be useful in the course of my researches. This turns out to be something of an understatement, since he is a legend among Malagasy musicians, Etienne Ramboatiana [right], better known as ‘Bouboul’. A captivating, sparkling-eyed gentleman of around 65, he sits gently spinning anecdotes about his life and a rain of historical information that in a short space of time could fill a book about the history of the guitar in Madagascar and the origins of the high plateau style in Antananarivo.

Bouboul himself started learning violin at the age 8, taught by his uncle. At 12 he started learning keyboard at the school of music in Ambatonakanga and at 18 became the organ player of Andohalo Cathedral. The money the priests gave him was so small that he left to work in a music shop and so got access to instruments and gained experience of trumpet (playing to Miles Davis records!) and jazz saxophone. He worked with Odiam Rakoto who played variété in a night club.

Etienne Ramboatiana. Photo: Ian Anderson.

“We arrived in Mombasa. Then Maputo. The circus was a majority of Brazilian people with some Germans – a new family life. It was very interesting and I really liked it but it was not a normal life! We toured all over Africa and India, from 1958 to1965. I saw a lot of things and I gained a lot of experiences so I wanted to give that back to people. I started music teaching.”

How did Malagasy guitar styles evolve?

“Well, as we all know, the guitar is a foreign instrument but in the time of Ranavalona III [the last Queen of Madagascar, exiled by the French in 1897], the guitar, viola, ‘flûte traversière’ and mandolin all arrived together. The vazaha played those instruments and people just watched. We realised that the guitar was only an accompaniment to the mandolin. So the Malagasy wanted the guitar to be independent. We wanted it to sing a song not to only accompany. The Malagasy sang in harmony a lot, with breathing technique and lots of melodies, so we wanted the guitar to do all these. The Malagasy guitar style was born!”

“When people down here heard that the piano made a really high sound, they put the capo on. When there was a very bassy sound they changed the bass strings by re-tuning it into C and G to get what we call today Malagasy style. I changed my bass string into D because it’s just too much to change it to C. In Antananarivo, some people would even change that string into a piano wire to get that big bass note.”

“Since the piano was used for theatrical pieces, that’s what guitarists translated onto their guitar. Theatres were very French so actors and artists would even change their names to names like Rakoto de Mon Plaisir, Simon de l’Aurore. So the guitarists also changed their names to Ramistery [Mr. Mysterious], Rakasikety [Mr. Cap], Rajebo [Mr. Zébu] and that was how Razilina was made. In 1942, these guitarists would go out serenading. They wore caps, big clothes and scarves, and girls would come out. They had to stop around Faravohitra because if they continued upwards, they would get soaked because people from La Haute would throw dirty water on them. La Haute is a piano place. Faravohitra was the highest area a guitarist could go up to and then they had to go back to Ambodin’Isotry where they came from.”

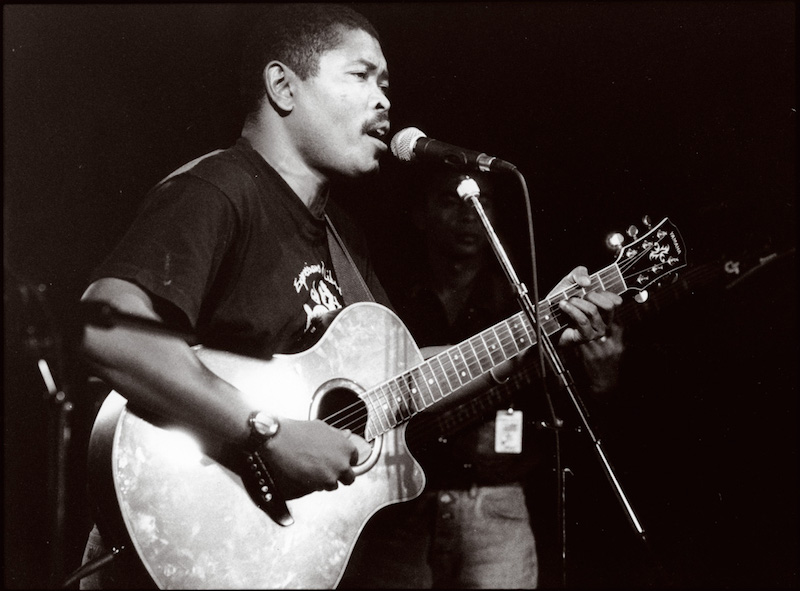

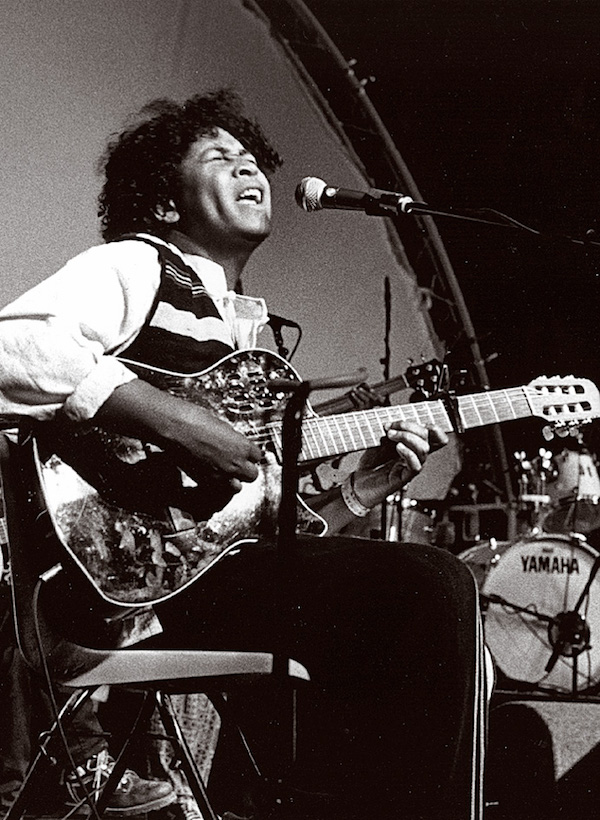

D’Gary. Photo: Ian Anderson.

“But you see, if you really want to find out about the Malagasy guitar style, it came from the way the Malagasy played the piano, but the piano was only copying the valiha. So the valiha is the origin of it all, then on to the piano and then on to the guitar. The piano did this little triplet and tremolo that it got from the valiha so whenever I teach guitar these days, all the students have to take a valiha lesson first. But the interesting thing is, where did this little style come from? Here is where we know that we really came from the East!”

“Things changed around about the second world war. The Malagasy got some style out of Charlie Kunz’s songs, a German who ran away to England. During that time, we always thought of abroad as very far away and that things from there were as if from another planet because they took 21 days to get here. So guitarists started to copy that style.”

“Then Randrianarivelo arrived. He brought another style of guitar. Then I arrived. One day, around 1951, Harry Hougassian, a Hawaiian guitar player and Mounitz (a Jewish player) played here in Madagascar. I was really taken by their whole way of playing. Harry played one of those guitars you put on your lap and slide it across and Mounitz accompanied him. [Hougassian was a celebrated Armenian player of the Hawaiian guitar, still alive and running a restaurant in Paris]. Every time a new guitarist arrived and brought a new style, others just took an inspiration from it and created another style again and so on and so forth. Hence we called that new person who brings a new style a ‘pillar’. Now all my students are learning my technique but they are all going to create their own style later on.”

What about the coastal guitar styles? “Guitar started here in Tana. In the West of Madagascar, they copy the Rumba Congolese. In the South, they copy South African style, but they only use these styles as an inspiration. I told Ricky [major Malagasy star singer: check fRoots #5] to do some research in his area about music because it is not good to come to Tana not understanding your musical background and at the same time come to a place where you do not understand its musical background! I always say to my students ‘If you don’t know where you are going, at least find out about where you came from…’”

A truly charming man.

In fact, the first interview I did specifically for this feature was with a player who really does know both where he comes from and where he’s going, the formidable D’Gary. Relaxing in our kitchen in London on a spring morning a year back, he filled me in on his life story, trials and tribulations.

D’Gary – his real name is Ernest Randrianasolo – comes from Betroka in the central south, and is of the Bara tribe. His father was a gendarme working in Tuléar, and in their camp was a musical troupe for which his brother played bass guitar. The 13 year-old D’Gary would take the guitar after the troupe stopped playing. Later he learned tsapika, that combination of southern African influences with different rhythms from the Masikoro region and the Vezo tribe, that was already played on accordeon. At the time D’Gary only knew one accordeon player in Tuléar, Regis Gizavo (fR173). “I did not even see one marovany player or any other traditional instrumentalists”, he now says.

This obviously deeply affected D’Gary; indeed he claims that everything he now plays has a basis in it. He’d never thought music would become his profession. “In Betroka, I was very famous for playing guitar but I did not particularly care. People in Betroka were playing sega and ‘blues’ [the common name for slow songs in Madagascar]. I suddenly became famous in Betroka because I brought the tsapika from Tuléar with me.” Guitarist Modeste Hugues Randriamahitasoa, now London-based, remembers Gary from those days.

“I played together with D’Gary, around 1977 or ‘78. We had a band, but Gary played alone. Sometimes when we played in Betroka he passed by and played with us. Like me, the people in my group taught themselves. We used to listen to the sound of the marovany playing for the tromba [spirit possession ceremony] and we liked it. When I was in Betroka, nobody else played in that style at that time. We were all trying to find a different sound and we started to retune the guitar. We’d go out into the countryside and spend the whole day trying to find tunings. It wasn’t just the sound of the marovany, it was the sound of the birds, or whatever was around.”

Eventually, D’Gary headed north to the capital. “In 1979, a group from Betroka was offered a recording with Discomad [the only substantial Malagasy record label, now called Mars]. They took me to Antananarivo and I agreed to go because I had to take care of my mother’s pension collection in Tana anyway. Charles Morin Poty [veteran record producer] of Feon’ala found me there, and I started to play as an accompanying guitarist for Feon’ala’s concerts.”

“I did not even have a guitar at the time. It was really during touring with Feon’ala that I started to have a lot of different styles. The avoria ceremony came back to my mind and I just automatically transferred this onto my guitar playing. I was already playing my own style by de-tuning the guitar, in hiding in my room.”

It’s at this point that the name of a man called Dida (once promoter of Antananarivo club Speedy and now owner of a studio in the East coast port of Tamatave) comes into the story. He’ll make other appearances…

“In 1981, Dida saw me practicing my own style before rehearsal. Regis saw me too and told to me not to show my style yet. I decided to start helping my mother in finding more money for the family because life was hard, so I settled down in Tana as a mercenary guitarist. Dida really made me who I am today. When I played as a mercenary, I just played and whenever there was a little bit of money I sent it back home to Betroka.”

“One day, I went to Maroantsetra on tour with Feon’ala and four of us decided to stay on. For six months (1986-7), although we were given shelter, food and everything, we just didn’t get anything out of it. So I went home by boat until I got to Tamatave. The moment I came out of the boat, Dida spotted me from his car despite my dirty, peasant look (since I came all the way from the countryside). Dida asked me why was I still a mercenary? I said because there was nothing else to do.”

“He then offered me his little studio, lent me his Takamine guitar, gave me food, shelter, took care of my health and even let my brother stay with me every now and then. Dida was my saviour! He ordered me to stop working as a mercenary and work on my own style in his studio every day.”

“To me, Dida is like a mid-wife who saved my life. He helped me a lot. Whenever I come back from my tours now, I always try to give him some money, but he refuses to take any. There is never going to be anyone else like Dida,” he says.

Apart from the solo tracks on that debut tape, there were others with a band. “The group was a bit forced on me. There was one guitarist who I chose to work with on that cassette. His name is Bloko. I wanted to help him out. He was an ancient and famous guitar player from Tuléar. There was also another one called Kaboto, Bloko’s brother, but he is dead now. Kaboto and Bloko were the best tsapika players. Another problem was that I was not a singer, I could not sing. I was not even ready to record but one thing was very important for me, it was the lyrics. I wanted the songs to be heard. My group started to be confused. Tata Rahely [a woman singer who now has a hot Mars cassette in her own right] was with us but she left to sing on her own. It makes me happy that at least Tata is still singing.”

D’Gary then related how, not long after this, two U.S. musicians spent a brief period in Tana making a series of albums, summoning him for a hastily arranged solo recording. Later, an American visit was organised alongside Dama, with whom he had never previously worked, and again a pressurised album session was sprung on the unprepared duo. D’Gary, angry about this in retrospect, deliberately repeated his material for the Horombé album (with his own group Jihé) on the respected French label Indigo/Label Bleu, with whom he remains to date.

Knowing that there are often more than two sides to any story, it’s better that I change the subject, and we talk about guitar styles, tunings and other players.

“Everybody who plays tsapika de-tunes the guitar. They change the E-string. That’s all. Mine is very complex. But during festivals, there is too much tuning to do, so I only use two. I have about 23 tunings but I’ve hidden them so far.”

“Although I lived a long time in Tuléar, my source is not tsapika, because it is very mixed with African stuff. My source came from the lokanga Bara [the traditional violin of the Bara people] and the avoria. Sometimes I combine the acapella way of singing together with the way the lokanga is played. Improvisation and tempo are the most important things for me. I have studied all this for a long time. I thought that the Bara tribe’s tradition was going to die because there are a lot of things disappearing so I tried to reproduce the lokanga or the jejy lava [similar to the Brazilian berimbau] or mpamalia [valiha, guitar and vocal together] on the guitar.”

“People always say that my guitar sounds like marovany, but it is not necessarily true. I also do lokanga but at the moment my band is from Tuléar so it is easier for them to adapt to the sound of the marovany than all the rest. The rhythm of my music comes from the footsteps of the malaso [cow robbers] who run away… One really has to experience the life of the people being constantly attacked by malaso in order to play the style I do.”

“The themes of my songs have never changed from the beginning. Our cows being stolen. Robbers who just get released two days after being caught. In Betroka, all police and gendarme are corrupt. The people whose cows are being stolen have also to spend their money on corruption. In Betroka, if there is peace, the gendarme are angry because they want people to fight so they can get money! They make taratasy poaka [anonymous letters] to encourage people to fight. Now people just decide to take the law into their own hands and they just shoot at those robbers. Bird guns became very big business because people now shoot at each other.”

“I only talk about Betroka because I do not know about the rest of Madagascar. Betroka does not have a Bara politician to stand up for its region so I sing about the situation instead. I am not afraid of my life, I shall talk about it forever. Since Alatsao Balansy to Mbo Loza [his latest, highly recommended, Indigo album, reviewed in fR167], it is not about looking for a seat, it is about stating a fact and telling true life stories. When the music gets back to Madagascar, the very small advantage I get is that they won’t touch my family.”

I guess the real seed for this feature was planted about 4 years ago. Haja (pronounced ‘Adz’), main guitarist with the band Solomiral, gave me a roughly recorded demo of himself playing solo electric guitar. It was the thing which finally switched on a light bulb marked ‘There are far more of these amazing marovany-style guitarists than I imagined!’ It blew me away, so much that I dubbed a copy for Ben Mandelson, GlobeStyle supremo and the man who, more than anybody else, kick-started the Madagascar mini-frenzy of these past dozen years.

Ben told me later that the cassette took up permanent residence in his kitchen tape player, the constant question in his head being “How does he do that?”. Some years on, Ben was finally able to find out by the clever method of booking Solomiral to showcase at Womex in Marseille. He, me and Mike Cooper all stood in the front row, shaking our heads and alternately asking each other “How does he do that?”

Seizing the opportunity of a tape recorder at hand, I got Haja’s story from him right there and then.

“I was a guitarist since I was 8 years old”, he says. “We were raised by a guitarists’ family. Our grandfather Ranaivo Betànana is one of them. We were all there but I was lucky enough to have the quickest fingers. I chose what I do because our grandpa played Malagasy traditional style guitar, from the Merina and Rasaraka tribes. Grandfather was a mechanic. He did not play guitar as a profession but for ceremonies, weddings, circumcisions… He had a twin brother (who is dead now) who played concertina with him. His open tuning can play so many styles of Malagasy music and this is what I do. I did not know anybody else who played to copy from: it was just inside of me. The strings are tuned in open C and the last string is adapted from the kabosy. Grandpa did only the first 5 strings of the tuning, and I added the last one.”

The family tuning is CGDGCD, but when Haja demonstrated it on electric guitar, he’d dropped it down another full tone to Bb/F/C/F/Bb/C. “We heard Grandpa, father and mom play music. Then wherever we went around the island, we heard something similar. We were listening to people like Rakotozafy, Bao Angèle, Mama Sana and especially Sylvestre Randafison. The base is the diatonic harmonisation. When I play guitar, I always start from this basis.”

“There were 7 brothers in Solomiral at one point but 2 have died. All of us play guitar but Mendrika decided to play drums from childhood, Fanaiky changed to bass guitar after being a solo guitarist in a rock band, Ny Ony now plays guitar in Tarika, Njaka also plays guitar and writes songs, and there is me, Haja, of course.”

Solomiral was started in 1976 by Bruno (who died) together with Mendrika and Haja. All the others were very young then, or not even born. In 1979 they put out an album. Haja was 14 years old.

A familiar name enters the tale …

“In 1986, we started to work as studio musicians at the Ravinala which is Dida’s studio. One day, he found me and asked me to work there rather than doing menial jobs. At the studio, we played basesa and zouk rhythms. We mainly worked there to make or arrange people’s songs. Then in 1989, we came back to Tana. Dida helped us to go to Tana to work with Tôty. It was really nice because we had met him in Tamatave at Dida’s place.”

Dida definitely has something about guitarists: Haja, D’Gary, Tôty, Iraimbilanja… and so many others even today. Oddly, though, Dida himself is a pianist. Although I’ve briefly met him a few years ago, he was unfortunately tied up with promoting a car rally (of all things!) when we passed through hot and humid Tamatave in mid-December so I never got the chance to get his overview of his various proteges. Another time …

Back to Haja. Is it correct to say you are playing marovany-style?

“Excuse me but this really is a guitar, not a marovany! We are only trying to get close to the marovany sound. Guitarists all have their own style. I like a lot of guitar styles but I also like my own. I am trying to promote a style in Madagascar, to polish the Malagasy guitar style.”

Any other Malagasy guitarists who should be heard? Earlier names?

“Freddy Ranarison. And since a long time ago, Etienne Ramboatiana who was the first electric guitar player in Madagascar – he toured around the world. There are a lot of guitarists to be listened to in Madagascar.”

There should finally be a Solomiral album for Mars before long. It has had a chequered recording history, partly due to the fact that their chosen style is vakojazzana, a thrilling mixture of vakodrazana [music and dance of the ancestors] and jazz, but they do also like to play some straight jazz/rock. Their current line-up also includes one of Madagascar’s best jazz sax/flute players, Seta, and keyboard player Rivo.

Unfortunately a comment to their producer by a helpful outsider that the few straight jazz/rock tracks might not be so well received on the Euro-American market as the rest seems to have been mis-understood as advice to rid the album of all jazz influence. So it was back to the studio to start again…

Clearly, a visit to Haja and Ny Ony’s elderly grandfather was clearly on the agenda on the very next trip to Madagascar. After bumping down an impossibly rutted lane (‘turn right at the dead doctor’s house’), we’re ushered into a typical neat one-room Malagasy home – a bed, table, four chairs and a sideboard all crammed into every available centimetre of floor space – and introduced to 87-year old Ranaivo Betànana (‘Ranaivo Bighand’). He talks animatedly, demonstrating styles and snatches of songs on a completely decrepid steel-strung guitar with an action about a cm high, capoed way up the neck. I turn to Hanitra and whisper “Joseph Spence”.

(I’m remembering how, when Tarika’s predecessors were asked to contribute to Fledg’ling’s Joseph Spence tribute album, they’d never heard of the Bahamas legend. But on being played his records Hanitra had remarked “There are old guitarists in Madagascar who sound just like this!” Reworking I Bid You Goodnight into a Malagasy piece presented few problems. But as usual, there are no immediate explanations for this similarity.)

What kind of guitar did you first play?

“I played gitara gasy [Malagasy guitar]!” “My real name is Ranaivo Jean Baptiste. My brother played a concertina. It came from abroad. He bought it from the mpihira gasy [travelling musical/ street theatre entertainers]. He would learn for about a month, then he’d sell the instrument and buy another one again until he was satisfied.”

“I first started playing guitar when I was 15. I heard somebody playing, nobody taught me. I first learned from the Makaka people. They are all dead now but I met up with them at La Haute Ville, near the Rova [the old royal palace, that was tragically burned down in 1995]. They only sang. Their songs were very easy, but that is what we saw so we learned their songs on our instruments. We figured out that the Makaka people’s songs could be done with only three fingers. From that it developed further.”

“People always complained about me borrowing their instruments. ‘Leave my instrument alone’, they’d say, ‘Your hand is too big!’ So I had to buy one. Our parents had all sorts of instruments: guitar, valiha, mandolin, accordeon… When we were children, we would queue up to see mom and dad and they would give us either valiha or accordeon and start playing. I also played a bit of valiha but never got very good at it. My father was a soldier, a shoe maker in the army, so he got some instruments. Otherwise, you had to go to the furniture maker and get one made because there were not any in shops.”

“I also played with Rakoto Frah [the legendary Malagasy flute player, now in the group Feogasy] but his playing hasn’t got any key so it is difficult to play with him!”

“The children, of course, refuse to learn what I taught them. They laughed and said: ‘What? Is this what we are going to play?’ I told them that they could start with that and later on they could always improve their technique.”

What does he think of Haja’s playing?

“I have heard it but I am not going to learn from him. I have my own pure Malagasy style and he does his in a different way. I really like what he does. He has progressed a lot. I blessed him to wherever he wants to go and wants to be. He is now leading a group. I cannot go anywhere any more because I am old now.”

F

inally, to the other marovany-style guitarist who European audiences are familiar with – the nimble-fingered Dozzy from the family group Njava (as featured on our cover compilation CD fRoots #10). It’s back to the south, where we started …

“I play marovany-guitar, and the first time I heard anybody play like this was a long time ago in Tuléar, in 1978. So then I started to listen to the marovany and play in this style. A lot of Malagasy guitarists play like this: in Tulear you have electric guitar players like Bloko, and I think it started around the early ’70s. When I was young I played with a lot of musicians in Tulear – they are old now – and I think that this style was already there, from say 1972 or ’73.”

“When I first started to play marovany-guitar, my tuning was an open G [DGDGBD]. All the guitarists were playing in this tuning. Then there was one guitarist I liked, the guitarist of Emmylou Harris, I listened a lot to that music. I’ve tried to develop, with around 8 different tunings, and I have my own style now – working a lot with the rhythmic pattern. If you play with the katsa [shaker, often a small tin filled with grit, on a short handle], you have to work to understand the patterns.”

“I’ve tried to listen to these Antandroy guys who play the lokanga: it’s something special, it’s very different from the marovany. I don’t want to mix these styles together, but I want to understand them, how the patterns work. It’s important to do that. Then, if you play them really clear, not dirty, maybe the European people can understand them too.”

“I didn’t know those musicians like Haja or D’Gary. Every musician has their own way, their own style. There are many guitarists in Madagascar, but no real big heroes. My way was just to stay in Tuléar. I first composed a song in 1985, already with the marovany guitar. When I started to play guitar it was for listening: at home, with the family, with nice harmonies and the guitar.”

“I never played the guitar-marovany for dancing. You would never use it for the tromba – people wouldn’t want it, they respect the marovany. But for circumcision, the bands who play for dancing have guitarists who play marovany-style, playing tsapika, but I never played that.”

“I think the guitar is now like a traditional instrument in Madagascar. A lot of people are interested to learn this style, but we need good teachers, we need schools, because it is difficult. I would like this style to be like flamenco guitar, a specialty that people will know everywhere.”

So there we are. Everywhere and yet hardly anywhere! And there are of course many players that I’ve missed and many more that I haven’t even heard of yet.

Another time …

One last thing that I still can’t figure out is this. In 1988, in Ziguinchor, Casamance, southern Senegal – a whole huge continent away – I recorded the brilliant guitarist Pascal Diatta. I noted in passing in these pages, in a feature which became sleeve notes to his subsequent Simnadé album, that his playing – supposedly influenced by Balanta xylophone – had elements which reminded me of the Malagasy valiha. Bear in mind that back then my knowledge of Malagasy music was mostly from a few live gigs and the pioneering GlobeStyle and Ocora collections. But after spending the entire ’90s completely immersed in this stuff, Pascal Diatta’s style sounds even more Malagasy to me. Explain …

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)