Lord Buckley

Ian Anderson tells the story of the noblest wig bender of them all, the blessed Lord Buckley …

Originally published in fRoots 194/5, Aug/Sept 1999.

To swiftly recap, in the March 1999 issue I was rambling on about shared enthusiasms in my Editor’s Box, in particular about how an unfeasibly large number of roots music people of a certain age treasure the works of a long-gone man who went under the name of Lord Buckley. I mentioned that for years I’d been trying to figure out a justification for running a piece on him in fRoots, and concluded by saying that if I didn’t get immediate complaints about the notion, I might just do it. Amazingly, not a single complaint, but instead a deluge of emails, letters and calls from all parts of the globe saying “Yes!” Well, if the grumpy old editor can’t indulge himself on the occasion of the 20th anniversary, it’s a sad old sphere, and if it has grown into a full feature, I can only blame it on you crazy readers out there.

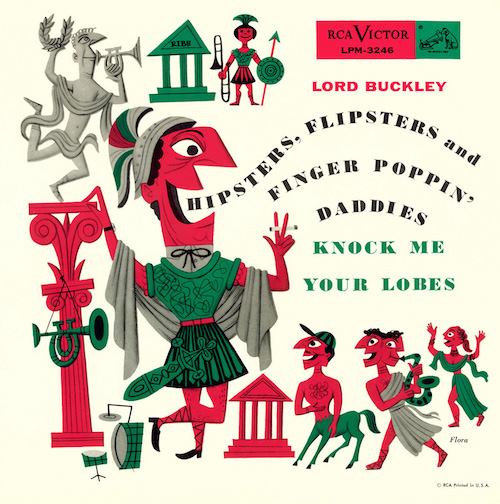

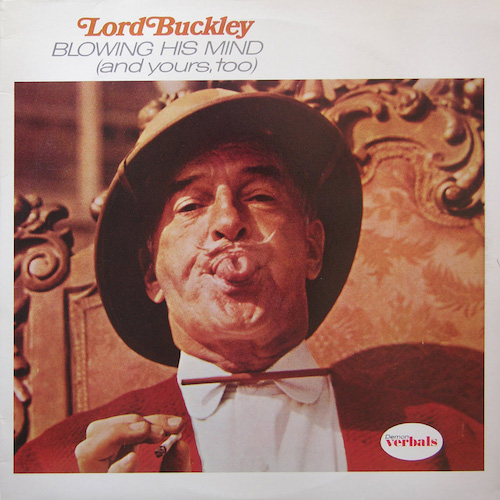

Where to start? You remember the first words of Transglobal Underground’s Nile Delta Disco, “Hipsters, flipsters …”? That was a direct quote from Lord Buckley’s reworking of Marc Antony’s funeral oration from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Willie The Shake, in which “Friends, Romans and countrymen, lend me your ears…” magically metamorphosises into “Hipsters, flipsters and finger poppin’ daddies, knock me your lobes…” in Buckleyspeak, Hip Semantic. He worked up epic monologues on all kinds of themes, some literary, some biblical, some historical, and some just from out there in the far-gonasphere. Perhaps his most celebrated work was the story of Jesus (The Nazz) but others included Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, tales of Nero, Ghandi (The Hip Ghan), Jonah & The Whale, explorer Alvar Nunez Cabaza de Vaca (The Gasser – which commences “You heard about Vasco de Gama the Island Bumper?”) and Columbus (The Hip Chris), The Bad Rapping Of The Marquis De Sade, Dickens’ Scrooge and Poe’s The Raven. He was a genius with the English language and the rhythm of delivery, described recently by writer Douglas Cruikshank as “the Charlie Parker of talk, the Fred Astaire of the tongue dance, the Paganini of prose.” They’ve even staged dance choreography to the rhythm of his recordings. He’s my all-time favourite storyteller.

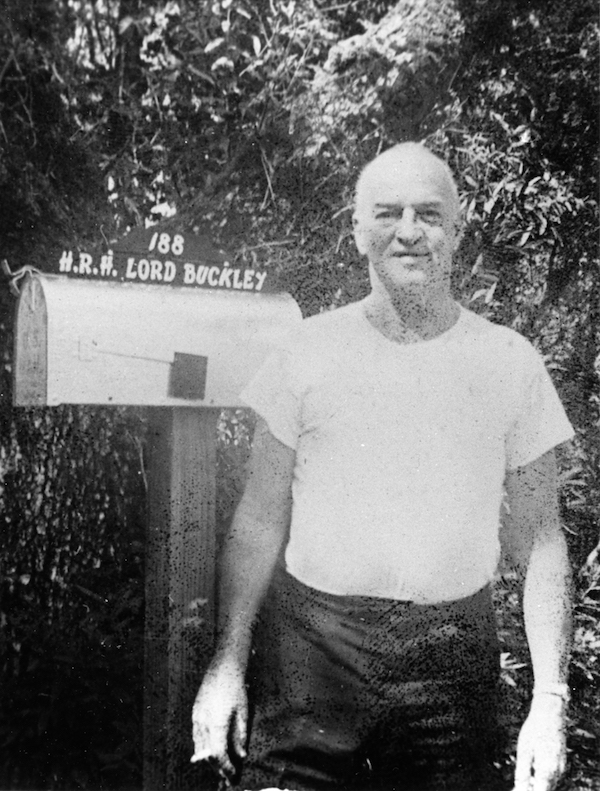

Dick Buckley 1930s-40s

Richard Myrle Buckley was born on April 5th 1906 in Tuolumne, California, one of ten children. His father, William Buckley, had emigrated to America from Manchester, and his mother Annie Laurie Bone Buckley, although American born, had parents who had emigrated to Seattle from Cornwall. As a child he was said to have earned coins from wandering cowboys by singing with his sister Nell on the streets; later he worked as a lumberjack before heading south to Mexico to meet up with his brother to become a labourer in the oil industry. He never made it: in Galveston he fell in with a Texan guitarist and somehow got diverted into show business, doing their first gig at a theatre in San Antonio.

In the late ’20s and early ’30s, depression time in America, Dick Buckley made his name alongside Red Skelton as a humorous MC for the then-current craze of dance marathons and walkathons. He worked widely in vaudeville and the speakeasies, hooked up with jazz musicians, became a personal favourite of Al Capone (who set him up for a while with his own night club) and is said to have acquired an altogether notorious lifestyle. When you start reading the tales of Buckley, there are numerous extraordinary anecdotes about his entertaining antics, stunts and scrapes. (At the end of his career, he did voice-over for a gem of a beat-era cartoon called The Wild Man Of Wildsville: it could have been named after him). During World War II he entertained the troops and toured with Ed Sullivan, who was later to regularly feature Buckley on his influential US TV shows, and by the ’40s was working in the casino cities of Las Vegas and Reno. Later still, he even appeared in a Hollywood movie with Marilyn Monroe and Ginger Rogers and did a walk-on in Spartacus.

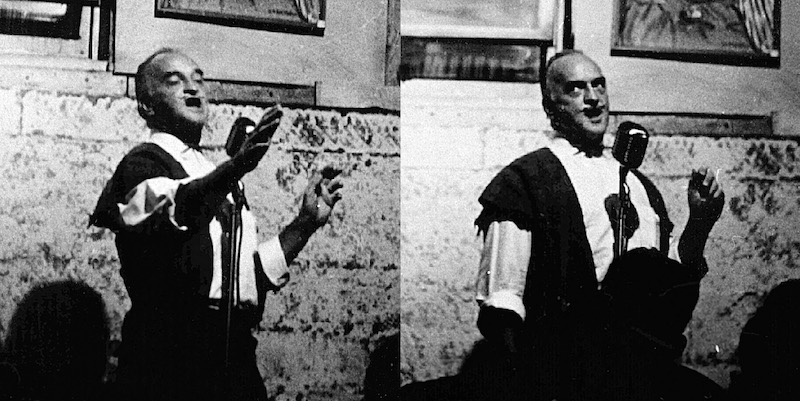

Buckley in action. Photo: Charles Campbell — Lord Buckley Online

“He almost went broke, starving to death, doing this interpretation but he could not stop himself,” said Buckley’s daughter Laurie when I called her at her Las Vegas home this summer. “Mother had encouraged him. So little by little, in the quiet times in the clubs in the late part of the night, he’d begin to do these monologues. Harry The Hipster, a beat hero who wrote Who Put The Benzedrine In Mrs Murphy’s Ovaltine? said, when he first heard dad’s stuff when they were working together, that he was doing his AA act, because they used to go to Alcoholics Anonymous together. But eventually it was everywhere that he could do them.”

In the early ’50s, Buckley’s first two albums were released on the Vaya label (some of these recordings, including the definitive Jonah & The Whale, can be found on the CD His Royal Hipness, Discovery/Elektra). In 1954, the family moved west to Hollywood, settling in Topanga Canyon in a large house dubbed “The Castle”. Oliver Trager, who has nearly completed a biography of Buckley [published in 2002 as Dig Infinity! The Life And Art Of Lord Buckley], describes him as the “Hollywood hep-cat in residence” and reports that his admirers included Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jnr.

This was where Buckley distilled and composed his greatest works, while the beginnings of the beat era were swirling around him. “He was the only one who said wonderful things about the beat generation,” says Laurie Buckley. “When everyone was putting down the James Deans and the motorcycles and the Marlon Brandos, he was saying how beautiful they were and how they represented a new age and a new time. I’m sure that Lord Buckley must have met Kerouac, they all struggled in the same struggle. Allen Ginsberg loved Lord Buckley. As much as they tried to put down the beat generation, we’re all living like them now. They were giving us highlights of our future.”

History says that Rambling Jack Elliott and Derroll Adams first met up in a Topanga Canyon house owned by actor Will Geer where Buckley was part of the scene. “I was amazed by his wonderful talent and storytelling… saw him do it twice, once at a nightclub in Hollywood called Cafe Renaissance across from Ciro’s on Sunset Boulevard…”, Jack reminisced to Paul Kahn earlier this year.

Central to that scene was a health food café in Topanga Canyon run by Bob DeWitt and his wife Zoe, where Buckley had set up The Church Of The Living Swing not long after moving to the area. Singer Dorris Henderson met him there later in the decade. “They were fans of folk music and I was singing at the folk clubs like the Troubadour and the Ash Grove where they met me and invited me up,” remembers Dorris. “That’s where I met Lord Buckley several times. He did a couple of concerts up there for Bob. Every Sunday they used to have folk people dropping in, and he heard me sing up there and asked me if I’d accompany him on these concerts he was doing at the Ivar Theatre.”

Dorris Henderson

The 1959 Ivar Theatre concerts were recorded and released by World Pacific (later in the UK some of these tracks made up the Liberty album that caught me). This most famous version of The Nazz has Dorris singing Rock Of Ages in the background, whilst behind the altogether more serious The Black Cross, a harrowing moral tale of a southern lynching that was later to be performed by Bob Dylan, Dorris is to be heard singing Cumbaya. Later, after moving to England where she’s lived since the early ’60s, the records caught up with her one day when visiting Collett’s Folk Shop in London. “I wasn’t aware at all that people in England knew of Lord Buckley until Gill Cook said ‘We’ve got some Lord Buckleys in, have you heard him?’. I said ‘Yes, I’ve met him’ and so she played the album and I said ‘That’s me!’”

Laurie Buckley was still a young child at this time. “I was at the Ivar concerts. Dad put us right up on stage. We could sleep across the piano. The concerts were all early in the morning like 1.30 because there were no stages for Lord Buckley to perform, so he started renting the Ivar Theatre. He just loved the theatre and wanted it to be like that all the time, which turned out to be everywhere we went, it didn’t matter. In the grocery store, down the street, he performed everywhere. To go grocery shopping with Lord Buckley, being in a line at a grocery store, was brilliant. I’d have thirty more friends than I had before I went in there.”

What was the ‘real’ Lord Buckley and what was the stage persona, then? Dorris Henderson assured me that “it wasn’t just a stage performance. He was just like that all the time. Off and on stage he was the Lord Buckley. A very stately manner.”

Laurie Buckley confirms this. “He was always that way, there was never a slip. He spoke very clearly, it was always very British. He had his moments that might have been quieter than others but it was always there. The whole Royal Court was just a royal court of love, whether you were the millionaire or the alcoholic guy that dad brought home from the AA meeting. It was always a highly stimulating atmosphere, musicians, artists, actors and actresses, always a collection of interesting, interesting people. He just had such tremendous insights into lives and souls, he had kindness and compassion and he never put people down. I might look over and say ‘what an asshole that guy is,’ but he’d have said ‘well, he’s just not himself today’! He could identify the negative in people but he never used it against them.”

“To show you how square we were as kids, I did not realise until I was in my early twenties at the first Renaissance Fair we had here in Las Vegas, and I heard these words that only my father would speak. I looked over and there’s this hippie dude on bales of hay on a stage and he’s doing Jonah & The Whale. So I go over and I’m sitting there listening to him and it was only then that I realised what the great green vine Jonah was smoking was!”

Buckley’s demise was as tragic as it was unexpected. Not long after a final recording for World Pacific in 1960 (on the CD Bad Rapping Of The Marquis De Sade, World Pacific), he’d travelled across country via a stint at Chicago’s Gate Of Horn to appear at the Jazz Gallery in New York’s Greenwich Village. He came up against the corrupt Cabaret Card system, dating back to the Prohibition era, and had his card confiscated by the police, supposedly because of a long-forgotten drunkedness conviction from the ’40s, more likely because he didn’t pay the right bribe. A high-powered group of people from New York’s intelligentsia formed an Emergency Committee to deal with the affair, but shortly before it came to court, Buckley had a stroke brought on by the stress and died on November 12th. That December, Dizzy Gillespie and Ornette Coleman played for a memorial benefit for the Buckley family at the Village Gate.

Even better for web people, there are endless hours of fascinating reading at Lord Buckley Online – www.lordbuckley.com It includes an extensive discography, lots of interviews, and the truly wonderful Buckley Hipesaurus, “A glossary of His Lordship’s swinging verbiage,” indispensible for cutting down on those all-night stylus frenzies.

Thanks to Laurie Buckley, Dorris Henderson, Michael Monteleone, Dick Waterman, Sid Soffer, Paul Kahn, Ken Hunt and Roger Armstrong, and to the writings of Oliver Trager and Douglas Cruickshank which I have relentlessly pillaged for biographical information.

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)