Fear and Loathing in Madagascar … 2001/2002

Originally published online 30th April 2002

All friends of the Indian Ocean Island of Madagascar were horrified at what unfolded there from December 2001, with virtually no detailed coverage in the UK or international media and very little apparent diplomatic attention by Western governments preoccupied with Afghanistan, the Middle East, Zimbabwe and French elections.

For those who don’t know it, here is a precis of the story so far. First, some history to give context.

Madagascar was unified during the 19th century by the Merina kings and queens from the highlands, based in the capital Antananarivo. The urban areas, with assistance from Victorian Britain, had achieved a relatively high level of education and industrial development.

The island was colonised by the French in 1897, exiling the last Queen Ranavalona III, and remained as such until independence in 1960. The familiar colonial “divide and rule” tactic had been employed, so that when a major and bloody independence uprising took place in 1947, the political groupings associated with the coastal regions sided with the French as they were encouraged to believe that independence would mean a return to Merina domination of political life. The uprising was quelled with the use of black African troops by the French (demonised thereafter as ‘Senegalese’) and around 100,000 Malagasy died, mostly in the highlands.

Ranavalona

Ratsiraka changed tack, opening up the economy to the West. In 1991, the country went on a 9-month general strike to depose him: he finally lost control after ordering his presidential guard to fire on a peaceful demonstration, killing at least 100. He lost the subsequent election, but the new president Albert Zafy proved incompetent. In the 1996 election, apathy was so high that Ratsiraka was returned to power on just over 50% of a 10% turnout. One of the last of the old-style African dictators, he continued to enrich his family through widespread corruption and intimidation.

In December 2001 there was another election in Madagascar (size: bigger than France; population 15 million; strategic and resource importance to the West – nil). All independent observers agreed the election was widely fraudulent and that the main opposition candidate Marc Ravalomanana, previously the mayor of the capital Antananarivo, defeated Ratsiraka by a clear majority, more than 50%. Even Ratsiraka’s own election results, counted by a personally installed High Constitutional Court, conceded that Ravalomanana had outvoted him. However, they claimed it was not by quite enough to avoid a second round, fully expected to be marred by even wider fraud, bribery and intimidation than the first.

The population went on general strike. Sometimes over a million demonstrated daily, peacefully, in the capital. The churches, judiciary and civil organisations joined together in support of the demonstrators. The army refused to intervene. The people declared Ravalomanana as their new President and swore him in. Ratsiraka declared martial law and a curfew, but the people ignored it and sang and danced in the streets all night. The army and police stood aside. Ravalomanana appointed new ministers and the people swept them into their offices. The army and police still stood aside in all but one instance (when there was a massacre at the Prime Minister’s offices, barely 400 metres from where my family there live).

Tsiranana

Ratsiraka, unable to accept defeat, fled the capital. He holed up in his power base, Madagascar’s main seaport of Tamatave (Toamasina) in the east, which he self-declared as the new capital and insisted he was still President (even though constitutionally his mandate ran out on February 9th). Initially, his thugs simply barricaded the main road from Tamatave to the highland capital Antananarivo, cutting off fuel and other essential supplies. But as things went on, the situation dramatically worsened. Ratsirakistes dynamited important bridges on all the major roads from all serviceable ports to Antananarivo. His mercenary gangs and remaining loyal army/ police units opened fire on peaceful demonstrators again, killing and wounding.

The central highlands – 4 million people or more – became devoid of petrol and fast ran out of medical supplies and many staples. Already poor families had no income for months as businesses ground to a halt and the banking system virtually shut down (earlier, before the Ratsiraka clan fled Antananarivo, his daughter Sophie was reported to have used trucks to clear millions of pounds worth of cash from the central banks, some of it apparently used to pay the gangs to cause trouble). The only thing Antananarivo had in its favour – apart from the unity of its people – was that its power supply is hydro-electric. And its people, who joined together to set up their own system of barricades to keep the terrorists out of the city, and foil plots to kidnap or kill their new leaders.

Virtually all the deaths and injuries in the crisis came about as a result of activities by Ratsirakistes. Whatever misgivings one may have about new president Ravalomanana’s close links with the church, at least this means his majority supporters were almost exclusively non-violent.

My involvement with Madagascar has first and foremost been with its music, and a family there by marriage. When I first went there 12 years ago I was shocked by the levels of poverty of the worst off in its society, who had living standards far lower than anything I’d seen in Africa. It was glaringly obvious that the single most important thing which would help Madagascar develop a viable economy was to first build an infrastructure of roads and communications in this vast island.

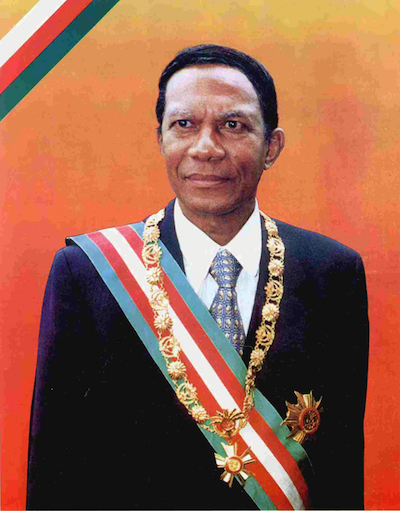

Ratsiraka

In late March, the European Union representative in Antananarivo, along with the local German, French, UK, Japanese and US ambassadors, pointed out that half of the grants given to Madagascar in recent times were to develop this infrastructure and pleaded for the barricades to be lifted. But with these roads now made completely impassable – and this is long-term impassable – all the businesses that depended on them to import materials and export goods are seriously disabled.

Ravalomanana

Meanwhile, there were no long-haul flights to Madagascar: Air Madagascar’s planes were grounded in Paris, Air France stopped flying because of safety issues and the imposibility of refueling. We were unable to send any assistance from Europe, either physically or financially. Just about the only thing any of us could do was put pressure on our media to report this situation properly, and so put pressure on our governments to intervene. This has not so far born and notable fruit.

The situation deteriorated fast. For the first time since independence in 1960, units of the Malagasy armed forces with conflicting loyalties started fighting against each other, bringing a rising toll of deaths and injuries, including of innocent foreign bystanders. What had been a largely peaceful revolution on the side of Ravalomanana’s supporters began to turn violent through frustration caused by the penury in Antananarivo. Petrol that was 4,000 FMG per litre now cost 40,000 on black market – that’s £4.50 a litre ($US 6.30), meaning it cost £140 (US $200) to fill the tank of a small Renault 4. Salt that was 250 FMG a packet became 7,000; charcoal which most ordinary people use for cooking was 6,500 FMG for a sack which lasts a family a week, rose to 70,000. But supplies became virtually non-existent, and this in a country where the average salary is 250,000 FMG (£30) and wages had not been paid for months.

Finally, on April 16th, under the auspices of the President of Senegal in Dakar, Ravalomanana and Ratsiraka were brought together for negotiations. An agreement was eventually reached on April 18th that the disputed first ballot of December 16th would be recounted and the barricades would be lifted, as Ravalomanana had insisted all along. In the event that Ravalomanana’s clear majority was not confirmed, a government of national unity would be formed for six months, at the end of which a presidential referendum would be held, supervised by the United Nations, European Union and Organisation Of African Unity (although policing voting in the vast Malagasy rural areas would be virtually impossible).

This sounded promising, but whilst Ravalomanana’s camp proceeded to follow the letter of the agreement, removing the protective barricades around Antananarivo, Ratsiraka stayed in France and his followers refused to remove the economic barricades from the ports. There were widespread reports of a “secret” extra clause of the Dakar agreement – which supposedly had been fixed by the French behind the scenes, but allowed to be seen as a diplomatic victory for the OAU – to allow Ratsiraka to retire gracefully into exile during the expected referendum process, with immunity from prosecution for his family and cronies.

Shortly before the Dakar agreement, the Madagascar Supreme Court had finally anulled the December election results, ordered a recount, and reverted the High Constitutional Court to its previous line-up before Ratsiraka had packed it with appointees just prior to the election.

Meanwhile, there were no long-haul flights to Madagascar: Air Madagascar’s planes were grounded in Paris, Air France stopped flying because of safety issues and the imposibility of refueling. We were unable to send any assistance from Europe, either physically or financially. Just about the only thing any of us could do was put pressure on our media to report this situation properly, and so put pressure on our governments to intervene. This has not so far born and notable fruit.

The situation deteriorated fast. For the first time since independence in 1960, units of the Malagasy armed forces with conflicting loyalties started fighting against each other, bringing a rising toll of deaths and injuries, including of innocent foreign bystanders. What had been a largely peaceful revolution on the side of Ravalomanana’s supporters began to turn violent through frustration caused by the penury in Antananarivo. Petrol that was 4,000 FMG per litre now cost 40,000 on black market – that’s £4.50 a litre ($US 6.30), meaning it cost £140 (US $200) to fill the tank of a small Renault 4. Salt that was 250 FMG a packet became 7,000; charcoal which most ordinary people use for cooking was 6,500 FMG for a sack which lasts a family a week, rose to 70,000. But supplies became virtually non-existent, and this in a country where the average salary is 250,000 FMG (£30) and wages had not been paid for months.

Although the election result was clearly legal, and Ravalomanana had kept to the Dakar agreement which Ratsiraka had broken, the international community held back from recognising the elected government while the OAU attempted to broker more deals. Behind this was obviously the likelihood that any secret deal which the French thought they had stitched up to allow Ratsiraka to retire gracefully with his ill-gotten gains had come spectacularly undone. Meanwhile the threat of all-out civil war was being made, with further blockades and economic collapse.

Later developments

10th July 2002

On June 16th, Ravalomanana dissolved his government in order to appoint a fresh one of national reconciliation that would include former Ratsiraka supporters, though in the event he made only a few cosmetic changes. Shortly after this, further evidence of atrocities was uncovered in the north, and on June 19th a plane full of French mercenaries hired by Ratsiraka was turned back en route to Madagascar. The OAU met in Addis Abeba and decided to continue pressing for fresh elections, freezing Madagascar’s seat in the organisation. Ratsiraka returned to Tamatave. All of these events appeared to simply stiffen the resolve of the Ravalomanana government to end the crisis, and a previous suggestion of granting amnesty to Ratsiraka was withdrawn.

On Madagascar’s Independence Day, June 26th, the long awaited international recognition came from the USA. This also served to free up Madagascar’s currency reserves which had been frozen in Washington, making it possible to recommence imports of oil, medicines etc. Less than a week later, the French (having seen that they were going to get sidelined if they didn’t do something fast) recognised the new government and sent their Minister of Foreign Affairs Dominique de Villepin on a flying visit to shake Ravalomanana’s hand, call him Mr President, offer wads of aid and pointedly ignore Ratsiraka. Two days later, the entire Ratsiraka clan fled to the Seychelles in a plane from son Xavier’s company, and several other plane and ship loads of cronies ran for Mauritius. Within two days, Ratsiraka had ended up back in France, the Brickaville barricade had vanished and Tamatave had hoisted the white flag. The UK, China and most other major countries joined in recognition of the new government.

Much progress is now being made. but politicians being politicians and Ratsiraka being a devious old devil, everybody should still keep alert. In Tana the house of Moxe Ramandimbilahatra, President Ravalomana’s cabinet director and spokesman, was attacked with a grenade and the same happened to the house of the woman Deputy, Mathilde Rabary, who had compiled a huge dossier of Ratsiraka criminality for the United Nations. With too many loose arms in circulation, and the Ratsiraka clan’s propensity for paying street thugs to do their dirty work, there will probably be more of this (although his widely-loathed daughter Sophie, reputed to be behind this sort of action in the past, is in France with her father and the rest of the exiled family).

Hopefully Madagascar will now be able to get on with reconstruction and a speedy return to normality. International aid donors are making the right noises. The longer-term danger might be a repeat of the “Zafy scenario”. One hopes that Ravalomanana is an altogether smarter character who will be able to do the job, consolidate his support, keep the country politically awake and the international community’s eye on the case. The new government is promising that Ratsiraka and those responsible for corruption and crimes against the country will be sought out and put on trial, but if Ravalomanana’s team don’t match up to their promise, we could yet see the Ratsiraka clan attempting a future comeback – Sophie is rumoured to be groomed for the dynasty …

These may have been small terrorists doing their awful things locally while the big ones played their international games across the oceans, but they have hurt millions of ordinary people just the same, people who have no voice outside. Madagascar will need all the help it can now get to recover from this disastrous chain of events, and that means keeping the world’s attention on it.

Ian Anderson, July 2002

Much later footnote: January 2014

President Ravalomanana was in turn ousted in a military coup in March 2009, which placed a 35 year old ex-DJ, Andry Rajoelina, in power. Once again the international community and aid organisations would not recognise the non-democratic regime and withdrew financial support. The new regime changed the constitution to allow Rajoelina (who was barred from office by his age) to run for power. Fresh elections were continually promised but did not materialise for four years, during which time there was further impoverishment, environmental degredation and widespread corruption.

When the elections finally took place in 2013 with neither Ravalomanana nor Rajoelina standing (but with endorsed candidates in their places), the Rajoelina candidate Hery Rajaonarimampianina won with 54%, to further widespread and well documented examples of voting irregularities. And so it goes on …

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)