Clifton In The Reign

From 1966 to 1971, the Bristol Troubadour was the top ‘contemporary folk’ club outside London, one of the few with its own premises. Everybody played there. Ian Anderson looks back in wonder.

From fRoots 400, October 2016

The past is indeed a foreign country where things were done differently, certainly as far as the UK folk scene is concerned. In these days when there are hundreds of festivals, only a relatively small number of folk clubs (many of which are run by – and havens for – the elderly), and hardly any college folk circuit at all, it must be hard to conceive of how things were fifty years ago.

In 1966, Britain was in the grip of a folk boom. It had been catalysed by the one that had blazed across the USA earlier in the decade with Bob Dylan as its poster boy, energising a UK movement that had spun off from 1950s skiffle and Cold War, bomb-banning political activism and embraced a turn towards our own traditions. You could count the festivals on one hand but there were many hundreds of folk clubs. Every town and many villages – and nearly every university and college – had one, cities had lots.

If you didn’t have a club locally, or the one that existed didn’t suit your tastes, you simply found a pub room and started one. Organisers, audiences and performers all tended to be around the same age – mid-teens to mid-20s – and often interchangeable.

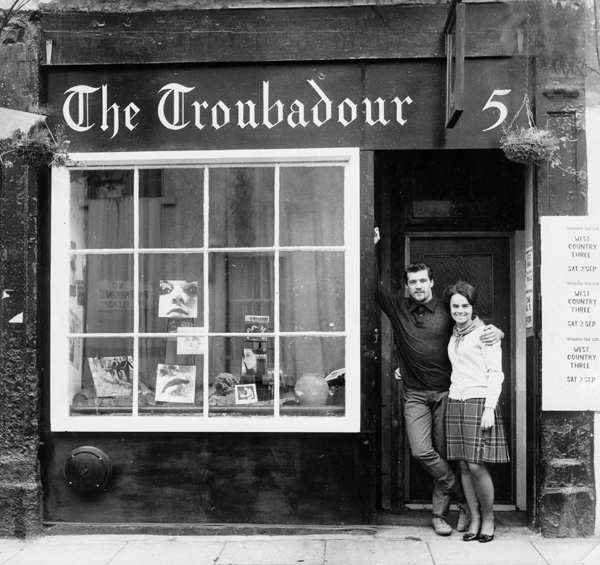

Ray & Barbara Willmott outside the club, 1967 (courtesy Ray Willmott).

Clubs didn’t have PA systems or stage lights, health and safety regulations barely existed, and it was commonplace to hitch-hike around the country to do floor spots and check out what was going on. Looking back, it seems like a year-round summertime with the living easy.

The majority of folk clubs in the UK back then ran in a pub or a licensed student union, and other than Les Cousins (the 1950s Soho skiffle cellar which had re-opened its doors as a dedicated folk

“In order to subsidise our now rapidly diminishing savings Barbara and I secured work at Bristol Zoo, Barb’ working in the gift shop and I was one of two keepers looking after the birds. After work, and sometimes before, my father and I laid a new concrete floor in the basement, rigged up old kerosene lanterns as light fittings, put in archways, two toilets, the coffee bar and rough plastered all the walls. I found a fellow who could make me twelve tables from solid pieces of elm and the benches were made from 12” x 2” solid lengths of pine which came from the lining of the hold of a ship carrying flour. Six tables upstairs and six in the basement was the original layout giving seating for ten per table.”

Rumours of Ray’s total folk naïvety were unfounded, it turns out. “It has often been said that I didn’t know anything about folk music when I opened the club but that isn’t strictly true. During my time in Australia I’d regularly visited the Folk Attic and the Troubadour Folk Club in Sydney where Trevor Lucas, later of Fairport Convention fame, and Martyn Wyndham-Read were regulars. Both later appeared at The Bristol Troubadour.”

But he was still a nervous man on the opening night. “As I stood at the counter inside the door of the Troubadour at 7pm on Friday 7th October 1966, my cash tin and membership book at the ready, I must have looked somewhat apprehensive as Barbara asked me why I was staring and turning a threepenny piece in my fingers. She wasn’t quite prepared for the answer I gave her but accepted it without any fuss.”

“I had just told her that this threepenny piece was the last of our savings and that if no one turned up to our opening night then I could not even pay the singers. Fortunately the audience came and from then on they came in droves.”

Ray’s diaries record that the opening night included Fred Wedlock, Anderson Jones Jackson (yours truly, Al Jones and Elliot Jackson), Bob Stewart and the Crofters.

W ithin what now seems like a few months, the Bristol Troubadour became one of the hippest places in town and built a reputation that soon spread nationally. Ray established good relations with the other clubs around the city, making sure not to book artists who clashed, and gained a loyal band of top class resident artists and MCs. Pretty soon a two-way musician axis formed between the Troub (as it became affectionately known) and London’s Les Cousins, with artists like John Renbourn, Al Stewart, The Watersons, Bert Jansch, The Incredible String Band, Sandy Denny, Jackson C Frank, Ralph McTell, Martin Carthy & Dave Swarbrick, Tim Hart & Maddy Prior, Shirley Collins, The Young Tradition, Michael Chapman, John Martyn, The Strawbs, Noel Murphy, Mike Cooper and many more, all appearing on its tiny stage. Later, into the ’70s, you could see early gigs by subsequent mainstream names like Jasper Carrott. For some, especially Al Stewart who immortalised the club in his song Clifton In The Rain, it became a second home.

And tiny it was, the stage cramped with anything more than a trio. Nobody looking at the building now – not even those of us who were regulars and in my case even lived for a while in the flat upstairs – can work out how the tiny premises at 5 Waterloo Street, Clifton, now occupied by a beauty clinic, can possibly have held what it did.

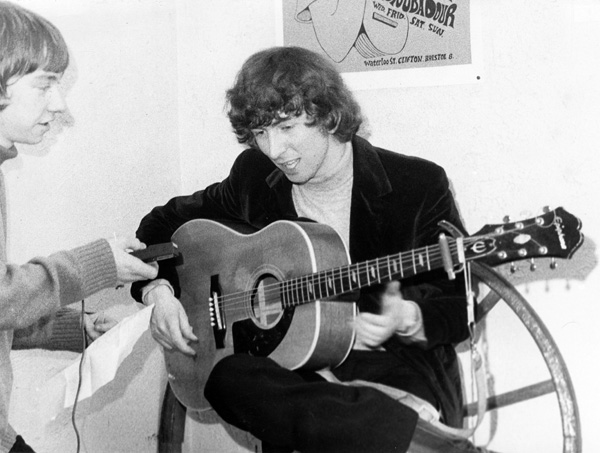

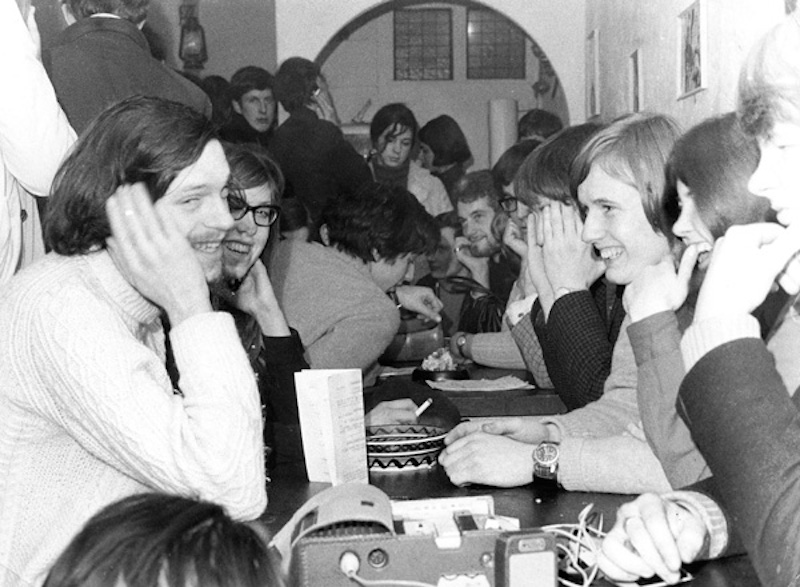

Entering the front door, past a little pay desk and through a curtained archway, you’d find the stage immediately on your right, with a big cartwheel propped at the rear. Those wooden benches and tables filled a roughly plastered, white painted room enhanced by artist photos, posters and a few ‘ethnic’ props. At the back was a small coffee bar. If you’re familiar with London’s current, award-winning Green Note café, the music room beyond that venue’s own curtained archway is nearly identical – except that once the Troub’s was unbearably full, a cramped rear staircase led down to a similar capacity cellar with more benches and another stage. On full nights, artists had to rotate between floors, duplicating their sets. For most of its first year, until the Fire Brigade insisted that a fire escape was installed, the only way out of the basement was the way in. 21st Century Health & Safety would have a fit, especially as audiences smoked back then! “Most of the time, the tables sat twelve at a squeeze, additional people stood wherever possible, and sat on the floor in the aisles which gave us a maximum audience of around 160 to 180,” reckons Ray.

Queues around the block were commonplace, and probably every student and young person for miles around gave it a try – the Melody Maker reported in 1970 that membership had exceeded 30,000 before counting stopped. The club expanded into running all-nighters, boat trips, bigger concerts. “I believe had we stayed in the UK I would have gone into concert promotion,” says Ray. “I put on the very first Adge Cutler & The Wurzels concert in Weston-super-Mare in January 1967, supported by The Crofters, Fred Wedlock, Sally [Oldfield] and Ian [Bray], Anderson Jones Jackson, Roger White and Big Brian. I came across one of the contracts with Weston-super-Mare Winter Gardens for the Adge Cutler concert I did there and my signature is witnessed by John Renbourn! John Renbourn and Adge Cutler on the same page! I put on the first Pentangle concert outside of London in the Victoria Rooms, Clifton, in December 1967, with an agreed fee of £100 guaranteed against 40 percent of the gross takings.” Later on, after Ray’s time, the club promoted a date on the first Steeleye Span tour at the same venue.

Ray and Barbara eventually sold up and returned to Australia in April 1969, leaving the Troubadour as a going concern. Though there was a very close ‘what if?’ involved at that point, because it was nearly bought by none other than Nic Jones and his wife Julia.

Julia Jones recalls that “One of the last gigs The Halliard did, shortly before Nic and I got married, was The Troubadour, and at the time Ray and Barbara were trying to sell. Knowing the band was about to go their separate ways, Nic decided we should buy it providing us with a home and a business. Their pet monkey, who had a room all to himself, was to be part of the deal. Both our parents had been shop owners and they offered to loan us the money and their know-how.

However, on doing the searches, we got cold feet on discovering there was only a short lease with no guarantee of renewal, and a rumour that Acker Bilk’s brother was about to open another music venue in Clifton. If it had been our own money we might have taken the risk, but not with parents’ money, so we pulled out of the deal. I was secretly relieved as I liked the job I had, didn’t particularly like folk music and didn’t enthuse about the prospect of being a serving maid behind the counter, and Nic got to laze around for six months reading Don Quixote and practicing the fiddle!”

Instead, the Troubadour ended up being sold to a local nightclub owner who put musician John Turner in as a manager, which coincided with the start of a glorious couple of years when the club hit its best-known era on the national stage.

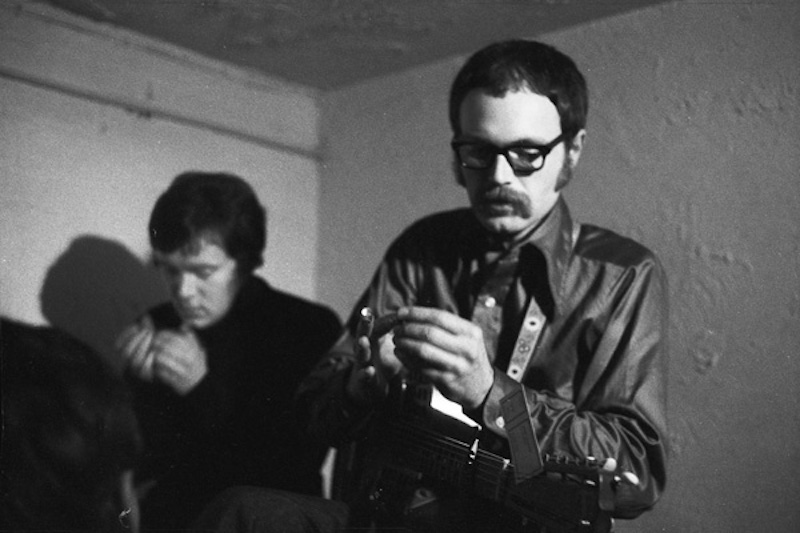

T he fact that it was open five nights a week, stayed open until the small hours, and didn’t have a drinks licence or PA meant that it had an amazingly beneficial effect on the local scene – a place where under-age music fans could be inspired, where musicians could try out new material or play with others, and you could drop in to socialise and unwind after a gig elsewhere. So musicians from all over the country started relocating to Bristol because of the scene centred on the club; others began professional careers there. Eventually some dozen Troubadour resident artists had nationally-released albums, including Keith Christmas, Shelagh McDonald, Al Jones, Steve Tilston, Dave Evans, Fred Wedlock, the Pigsty Hill Light Orchestra, Sally Oldfield, Hunt & Turner and myself.

The old Georgian part of Clifton where the club was situated was run down, dilapidated and bohemian in those days, a cheap home for students, artists, musicians, writers (Angela Carter lived just around the corner and ran another, more traditional, folk club with her husband Paul), beatniks and hippies.

So it was with an idea inspired by New York’s Greenwich Village that we started putting the club’s address as ‘Clifton Village’ on posters in 1970, and created the Village Thing ‘alternative folk label’ around it. Nearly 50 years later, Clifton Village has long-since become an actual thing, designated as such on maps and road signs to the great delight of estate agents and modern coffee shop and deli proprietors. It’s not the first or last time that artists have kicked off the escalating fashionability and property prices of an area (just ask Hoxton) but possibly the only one directly attributable to a folk club.

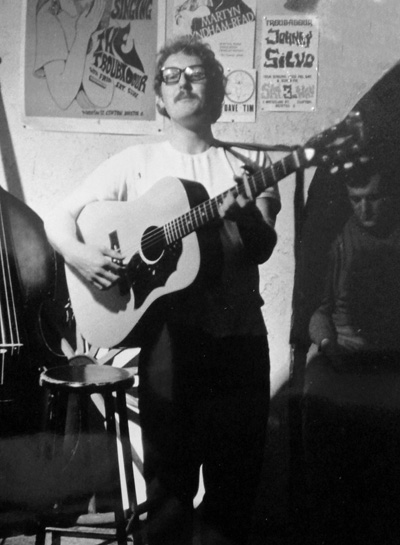

(Photo: Alan Cole)

To invoke another cliché, all good things must come to an end. In spite of continual and concentrated efforts by John Turner, final manager the late Tim Hodgson, and all the ‘name’ resident artists – a rota of whom played packed Friday nights for free to boost the takings – the second owner finally lost patience with his inability to coin it in and peremptorily closed it down in 1971, ending one heck of a stellar five year run which really did change many lives.

The 50th anniversary of its opening was celebrated with a big concert at St George’s Bristol.

It featured a mix of people who had played the club alongside younger West Country artists paying tribute to those who’ve gone: Michael Chapman, Wizz Jones, Jasper Carrott, Steve Tilston, Hot Vultures, Keith Christmas, Ian Hunt, Andy Leggett & Friends, Elliot Jackson, Jim Moray, Three Cane Whale, Jim Causley, Heg & The Wolf Chorus and Emily Jones. I chaired a panel discussion with Ray Willmott, Joe Boyd, Dave Evans and Sue Wedlock and there was a three week exhibition. The concert was followed the next day by the unveiling of a Bristol Civic Society blue plaque at the old Troubadour premises.

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)