The 1970s, Deleted

For the English folk scene and its myriad spin-offs, the 1970s are becoming the decade that history deleted. Ian Anderson has a go at correcting perspectives.

From fRoots 328, October 2010

It’s a great time for books and magazine features celebrating the musical spin-offs from the early UK folk boom into what was then called ‘contemporary folk’ or folk/rock and nowadays gets labelled with all sorts of bonkers designations like ‘psych folk’, ‘strange folk’, ‘acid folk’ and other sub-genres that never existed at the time the music was created. Wherever you look in magazines like Shindig, Mojo, Record Collector or The Wire there are constant references, and the bookshelves are rapidly filling – Rob Young’s excellent Electric Eden is just out and Jeanette Leech’s intriguing-looking Seasons They Change is due in November. Alongside this, reissues abound and vinyl that has rarity comparable to that of chicken molars sells for eye-watering prices on eBay, regardless of the reasons that caused the scarcity. A new history and set of legends have been created, particularly over the past five years or so.

The ‘f word’ has been devalued as a term of reference for a long time, way past the point where there can be any meaningful or entertaining discussion about what it means. For 40 or more years now, the American-led music business has used it as shorthand for ‘acoustic’ or ‘sings own songs with acoustic guitar’ or, these days, sometimes with the prefix nu-, ‘has banjo or accordeon in line-up’. Fine, call it what you like, nobody dies, and there are plenty of other useful if slightly unwieldy terms like ‘traditionally-rooted music’ to describe what the little abbreviated ‘f’ in our title covers.

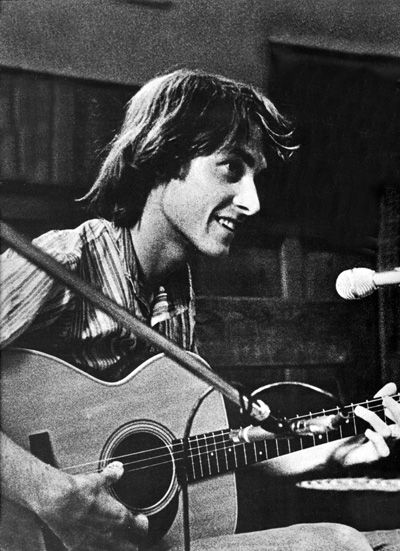

Chris Thompson, photo by Dave Mason

Approaching the new literature can’t, therefore, be done in a spirit of genre denial. “That’s not what I call folk” simply isn’t a valid remark, because everybody and their pawnbroker has their own different idea of what the term means – let alone the sub-genres – and having -folk as a feral -ism running wild across the musical landscape does produce some startlingly interesting bedfellows and discoveries.

Moreover, just as young men in greatcoats in the 1960s found their way from the Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac and even Jethro bloody Tull down tortuous paths to the likes of Charley Patton, because at some point the former had been on a bandwagon marked ‘blues’, how are we to know that a current purchaser of anything from Vashti Bunyan to Mumford & Sons might not end up five years later worshipping at the altar of Eliza Carthy or Harry Cox.

So terminology is not a problem and I’m as happy to participate in the ‘invent a sub-genre a day to keep boredom away’ game as anybody. Who and what’s included in the story of something-folk isn’t a problem either, the more the merrier. But what has begun to disturb me lately is what isn’t included. For history is being increasingly remoulded and its dusty files culled, along with a certain amount of over-mythologising and self-mythologising along the way.

“That’s not what I call folk”

simply isn’t a valid remark

Thinking of those 1960s blues days again, things gained stature almost by luck. Unlike now, when just about every pre-war blues record of any worth has been reissued, we only heard what was given to us. Sometimes, artists who’d only cut a couple of obscure sides 35 years earlier achieved surprising fame in the historic scheme of things simply because they found their way onto a reissue alongside contemporary giants.

Because of their inclusion in compilations by the ultra-hip Origin label, William Harris with his Bullfrog Blues or Garfield Akers with Cottonfield Blues were, in our eyes, just as important figures as hugely greater-selling and more influential artists of their era like Blind Lemon Jefferson or Blind Boy Fuller. To this day, ‘schools’ of artists like those around Dockery’s Plantation are much more revered in the scheme of things than their contemporary status probably justified (which has nothing to do with how great their music genuinely was).

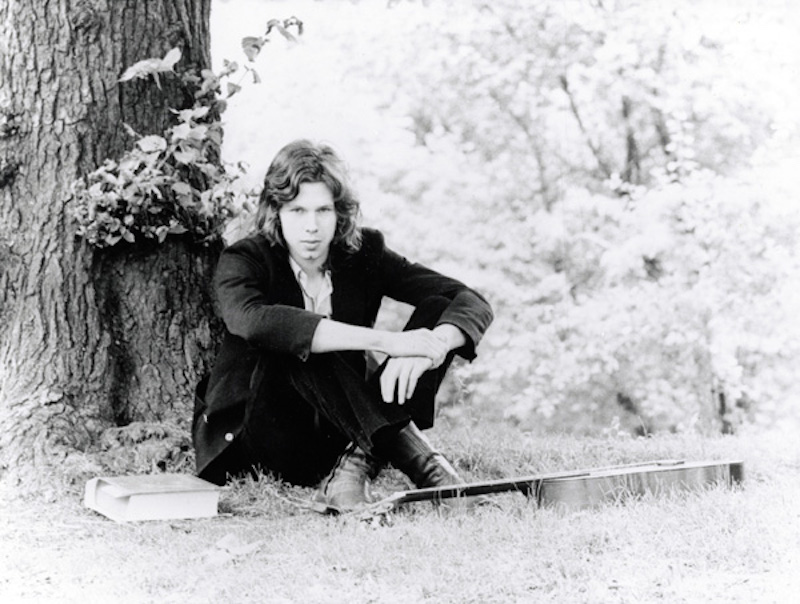

Nick Drake, photo by Keith Morris

So, back to the folk history thing. I’ve greatly enjoyed reading Rob Young’s thought-provoking Electric Eden, for everything that was included. But as I progressed through it, I started to have misgivings that it wasn’t the whole story. This is nothing I blame Rob for: he was only being born when much of the core music in the book was being created, and by the time he became interested in it, the tectonic plates of history had already migrated. It’s impossible for anybody coming later to hear the music in context, especially in the context of records that weren’t made and records whose place in history has been concealed by the mists swirling around others’ legends.

Dr Strangely Strange

The truth is, of course, that the majority of artists of the time didn’t do any of those things. Making records was far less common than today when everybody in the world – or at least the USA – gets to put out at least one CD of their own songs, and most had to get it together in an unremarkable urban bedsit or basement.

Of course it’s reasonable that tales are constantly retold and uncovered about the high profile, well-selling and influential bands of the day like Fairport Convention, the Incredible String Band and Steeleye Span. But strange cult status has grown up around certain artists like Vashti Bunyan and Nick Drake who, partly through their back stories, later achieved much greater fame than they did at the time they made their albums. Albums which, I could argue, only sound good out of context, compared with later things against which they sound ‘other’. At the time, stacked up against more interesting music of the day, they stiffed.

Who the fuck is Vashti Bunyan?

And here you have the beginning of how the mythology overtakes the music and artists’ actual achievements. I vaguely remember seeing Nick Drake in London’s Les Cousins, the haven for aspiring young singer/ songwriter/ guitarists of the day. The reason my memory is vague is that he simply wasn’t that noticeable, his music was definitely not outstanding among that of many other similar people around, and his performance skills were frightful. Quite why he attracted a record deal is a mystery. On a recent TV feature about Drake, Joe – a man who I greatly respect and with whom I’d rarely argue – came out with some statement about how Drake was so original and unlike anybody else at the time. “No he fucking wasn’t, Joe” – I bawled at the screen – “if you thought that, you didn’t get out enough!”

Joe Boyd was of course a visionary record producer, one of the greats, but at that time some of his ideas were possibly out of step with what the audience – and critics – expected. By the mid-’70s, in the wake of the success of American names like James Taylor and English acoustic songwriters like Al Stewart and Cat Stevens crossing over to the mainstream, there was a new audience for acoustic songwriters with denser production, rock rhythm sections, orchestras, keyboards, kitchen sinks and the like. At the time of Drake’s first release though, the main UK audiences were from folk clubs and colleges and still finding such things intrusive.

The reason my memory

is vague is that Nick Drake

simply wasn’t that noticeable —

his music was definitely

not outstanding

Al Stewart had been inspired by the orchestrations on Judy Collins’ In My Life album to go that route on his debut Bedsitter Images, for example, and it really wasn’t well received.

But whereas Nick Drake sank without much trace at the time, in spite of the benefits of mainstream distribution and promotion, our little Village Thing label working out of Bristol with much smaller resources could regularly sell several thousand copies of our releases by – I’ll argue better – singer/ songwriter/ guitarists like Steve Tilston, Dave Evans or Wizz Jones. Reviewers at the time praised the fact that their records weren’t overburdened with session musicians extraneous to how the artists generally performed live, because there was clearly a growing trend to do otherwise. And today, of course, with the huge decline in instrumental standards amongst landfill singer/ songwriters, those records sound astonishing by comparison.

Evans, Tilston and our other Jones boy, Al, may have been more popular performers and record-makers at the time, but they weren’t living in London or a country commune, recording for a major, produced by a ‘name’ or hanging out with members of one of the golden circles. Worse for legend, they didn’t disappear over the horizon in a gypsy caravan, come equipped with an iconic set of Keith Morris photos or terminate their own lives (though Al Jones did his best for commercial suicide by moving to Padstow and becoming a coastguard). On a sliding scale of mythology-creation points, they barely register. So far they’ve not turned into the Garfield Akers of their generation by being included in a taste-making compilation. Nor have they been fêted in any new-genre defining features like Richard Morton Jack’s ground-breaking April 2005 Strange Folk piece in Record Collector which established the likes of Forest, Trader Horne, Trees, Spirogyra, Vashti Bunyan, Comus, the Sallyangie and Synanthesia as Strange Folk royalty and sellers of old vinyl at unfeasible prices. At the time of original release, though, few people were that bothered about most of those bands. Often they only had a reputation at all because they’d been picked up by a major label A&R man and got their LPs advertised in Melody Maker and Sounds. That’s history for you.

Transatlantic had to find

a creative way to dispose of

over-pressings of Pentangle’s

post-Basket Of Light albums

One of the Village Thing stable whose original vinyl has at least got into the silly money stakes is New Zealand songwriter/ guitarist Chris Thompson, but that’s because his eponymous album, like Vashti Bunyan’s, only sold just over a hundred copies. This wasn’t through any musical faults of his own, though (as imminent CD re-release by Sunbeam will prove), but because faltering distributors Transatlantic had to eventually find a creative way of disposing of massive over-pressings of Pentangle’s post-Basket Of Light albums. Thus their vans curiously acquired a habit of being stolen and the contents – which naturally were bound to include a certain amount of other Transatlantic-distributed stock as well, to be convincing to the insurance company – were lost or destroyed (by fire, or dumping into a canal…). Many low-selling albums end up among the stock of cheap deletions out there depressing the market, but not Chris Thompson’s or his label-mates Lackey & Sweeney.

Michael-Claire (Mike Milner & Claire Hart)

History has been even less kind to the artists who didn’t manage to make it past the front door of a record label. You could possibly explain away the failure of the West Country’s popular Mudge & Clutterbuck by their hippy shambolicism (or a crap name). But why, for example, people like Anglo-American duo Michael-Claire (Mike Milner & Claire Hart) didn’t make the breakthrough is much harder to imagine. With great voices, songs, guitar playing and fabulous good looks, they played all the right venues of the day like Les Cousins and the London and Bristol Troubadours, appeared on the BBC’s radio folk show, even hung out with the gang in London’s popular post-gig café La Fiesta that included the likes of Sandy Denny and Trevor Lucas, but they never got a record out. Finally, in 2008, Italy’s Night Wings released their extraordinarily good 1971 demos – but only on vinyl, not CD, so they’re still nearly lost to posterity.

If received history has got the relative popularity and importance of certain songwriters and folk rock explorers out of kilter, it has nothing on the cruel hand dealt to most of the great younger exponents of traditional song and music of the day. For a while, most of the popular artists around the folk club circuit of the early ’70s who didn’t record for Topic were on Bill Leader’s Trailer label. It operated on pretty much the same shoestring and with similar basic equipment as we did with Village Thing, and was also distributed by Transatlantic. Beginning in 1969, by 1973 his catalogue included wonderful albums by Nic Jones, Pete & Chris Coe, Tony Rose, Dave Burland, Bob & Carole Pegg, Robin & Barry Dransfield (who made Melody Maker folk album of the year and reputedly massive sales for a folk album), Dave & Toni Arthur, Roy Bailey, Martyn Wyndham-Read, Swan Arcade, John Kirkpatrick, Alistair Anderson, Vin Garbutt and many more, alongside some fabulous traditional recordings on the sister Leader imprint. This was the era when things had moved on from the stern folk revival of the Ewan MacColl days and to a great extent set the stylistic foundations for the younger folk performers of today – particularly in the case of the Nic Jones albums.

Things had moved on

from the stern folk revival

of the Ewan MacColl days

Pete & Chris Coe, photo by Ian Anderson

So why have most of these artists been almost entirely written out of history, hardly appearing in any current literature, neglected by trend-defining journalists, their reputations only living on in the memories of older folkies and, increasingly their musical offspring (like Kate Rusby or Nancy Wallace) who grew up with their parents’ record collections?

Well, in the late ’70s Bill Leader sold his label, all the masters, to another company and later still – with no reference to Bill – it was all sold on to Celtic Music in Harrogate, run by one Dave Bulmer. For reasons that seem totally inexplicable to everybody who has ever heard the story, the famously litigious Bulmer has sat on his treasure hoard ever since, hardly re-issuing anything other than on badly packaged CDRs. Here you have a decade of such great importance in the evolution of modern British folk music, already being sidelined by the historians because it doesn’t tick the right London/ major label/ name producer/ intriguing back story boxes, and modern audiences simply have no access to it at all.

Modern audiences simply have no access to it at all.

Add to the equation the lost royalties to some great and deserving artists, then this ought to be classed as criminal behaviour, wouldn’t you say, or at very least evidence of insanity? If a luxurious 19-CD Sandy Denny box set – as described elsewhere this issue – is commercially viable, then a well-remastered, beautifully packaged, well annotated and memorabilia-filled box of the four Trailer label Nic Jones works, plus his Bandoggs album with Pete & Chris Coe and Tony Rose, ought to be what our colonial cousins would call a ‘no-brainer’.

Electric Eden does of course include loads of people who do deserve being written back into history – for example characters around the Donovan/ St Albans scene like the nigh-forgotten Mick Softley (who, nevertheless, did have the advantage of recording for CBS). And whatever you might think of Vashti Bunyan’s music, that’s a great story of her epic horse-drawn journey away from fame and fortune: few can match that other than the disappearing act done by the vastly under-rated Shelagh McDonald who some rank up there with or above Sandy Denny. And the mouth-watering advance sections I’ve seen of Jeanette Leech’s book indicate that it’s jam-packed with stuff about people I’m only dimly aware of, especially from more recent times.

The 1970s are, however, in great danger of becoming the decade that time deleted as far as histories of the English folk scene go. Its image may be warped by coinciding with the era in which some folk clubs, especially those in colleges, became hugely successful breeding grounds for the new stand-up comedy, but it was also the decade in which the Free Reed label began, bringing us the first flowerings of The New Wave Of English Country Dance Bands like The Old Swan Band and Flowers & Frolics, a hugely important and influential movement reshaping instrumental music and the ceilidh revival since, but which has been ignored by nearly every history. I tried really hard to get the producers of the Folk Britannia TV series to include such things, but they weren’t part of their pre-set, already rewritten history agenda.

There’s a yawning time gap

between Pentangle and

The Pogues, as if little

happened for 15 years

Instead, we still get endless repackaging of the 1960s Transatlantic catalogue, the 1970s Island store, and a yawning time gap between Ewan MacColl and Billy Bragg, Pentangle and The Pogues, as if little happened for nigh on 15 years apart from the bouzouki turning into an Irish traditional instrument.

So I’ve started in my own small way by getting some of the Village Thing catalogue back out there. Short of a commando raid on Dave Bulmer’s warehouse to liberate the Trailer masters or the invention of a working Tardis to take writers and musicians under 50 back to experience the 1970s folk scene for themselves as it really was, though, I’m really not sure how this sad state of affairs can now be remedied. But if I’ve piqued your curiosity, it’s a start.

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

The Cultural Boycott (2001)

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)