Koernering The Market

America’s most original folk blues stomper returned to the UK in summer 2010 for his first tour in nearly thirty years. Ian Anderson caught up with a hero.

From fRoots 325, July 2010 – incorporating some sections from an earlier interview published in fR150, December 1995

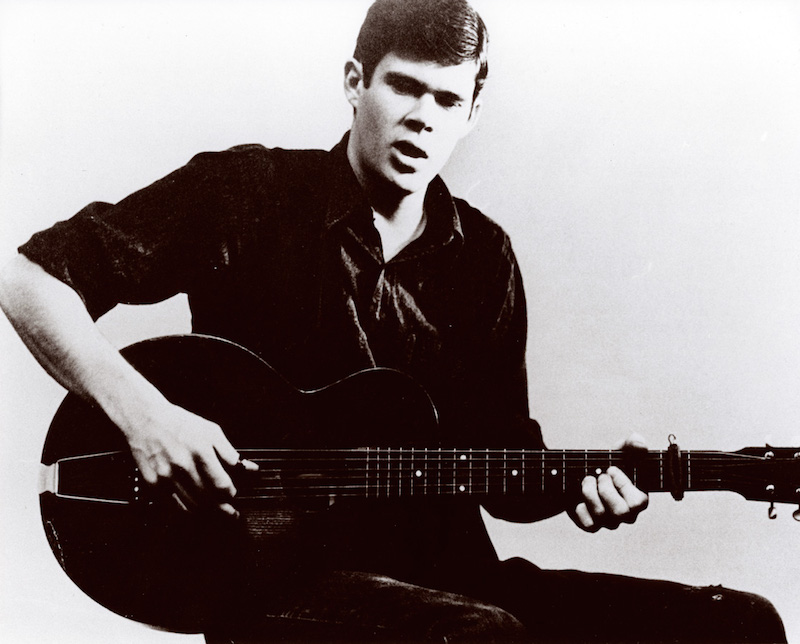

Spider John Koerner is an American national treasure, a genuine folk blues hero. Bizarrely, most of his fellow countrypersons remain blissfully unaware of this, in spite of his being one of the key figures of the 1960s folk boom, an influence on the young Bob Dylan, a recording artist for the revered Elektra label and admired by the likes of John Lennon. They ignore his continuing status today as a true stylistic original, and one of the few people still breathing life into the American folk song repertoire from the classic collections. Without getting all biblical about a prophet being without honour in his own country, there are times when I think he’s been more appreciated over here.

“The word inimitable could have been coined for Spider John Koerner,” said Martin Simpson last year. “A staggeringly singular guitarist and singer of blues and American traditional songs, he has influenced many musicians but no one has come close to his unbelievably funky guitar style.” In a relatively rare outburst of local acclaim, the New Yorker recently opined that “His influence on twentieth-century music aside, watching Koerner perform might be the closest you can get to understanding how, more than eighty years ago, Charley Patton alone on guitar kept a roomful of people dancing and partying until the sun came up.” Yet he goes glaringly unrecognised for the Lifetime Achievement Awards handed out by the folk establishment and government cultural schemes.

I asked Mark Moss, editor of American folk bible Sing Out! magazine, why this might be. “I think part of the reason for the lack of proper respect is that folks moved from fawning over the source singers/ players to lamenting their passing without ever giving just due to the first generation of heroes who saved that ‘real stuff’ from obscurity, longer ago now than that original music was when they revived it. The same is true, really, for a decent list of other folks who became templates/ guides to lots of early country and blues revivalists. I know I’m eternally surprised by how little coverage that bridge generation have got over the years. They wrote articles for Sing Out! more often than they got written about! Those first two Koerner, Ray & Glover records, especially, were an essential inspiration for a generation of players. No question. I know my copies were worn nearly flat!”

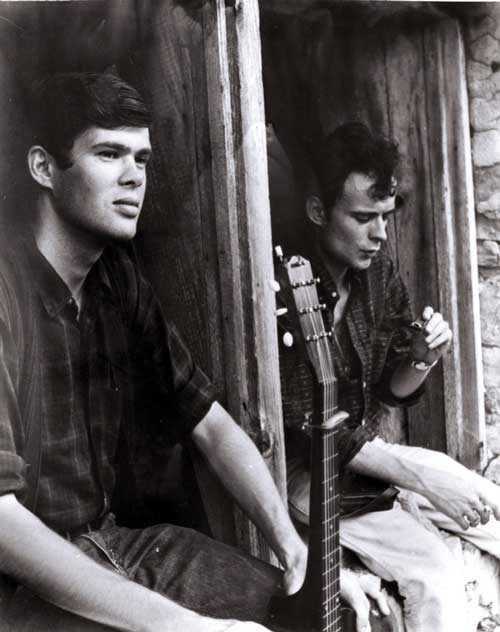

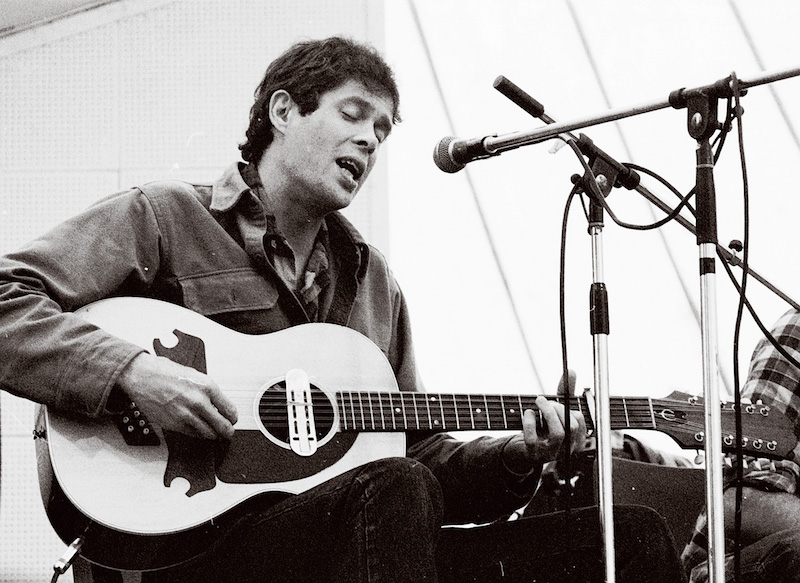

I became a fan of Koerner, Ray & Glover – a loosely structured trio with 12-string guitarist Dave Ray and harmonica player Tony Glover who were more often than not soloists or duos – through imported copies of that series of Blues, Rags & Hollers LPs. But it was in 1965 that Koerner himself blazed across my musical skies. Elektra released his Spider Blues, and he began solo touring in the UK.

Over the next couple of years, Koerner regularly toured the UK and I saw him perform on numerous occasions. I never tired of his early “hits” like Crazy Fool, Creepy John, Good Time Charlie, Whomp Bom, Good Luck Child and Ramblin’ And Tumblin’, and especially his trio of “epics”, Duncan And Brady, Hangman and Rent Party Rag, which he would spin out into free-association tall-tales lasting 10 or 15 minutes; never, I swear ever, even remotely similar two nights in a row. He was the only one of that era’s American white bluesmen who was really seriously admired by us chaps on the British country blues scene like Jo Ann Kelly, Mike Cooper and myself.

And I’d absorbed Koerner’s own comments on there: “You know that the white guys are not the same as the old blues guys and if you think they are, you’re crazy, but you still want to make good swinging music. Okay, once you have figured that out and start fooling with the music so that you don’t think so much, then you are doing some stuff, maybe even your own stuff. You start thinking about little rhythms – boombachika – and like that. You start thinking about little notes and chords that really work and you think how good it feels to snap the strings with your fingers and it’s a treat to beat your feet on the upbeat and put ‘em together and what have you got – bipity bopity blues and you know that’s right.” Bipity bopity blues! Eureka! Hero!

So he toured, he amazed with his style, his drive, his weirdly strung guitars. He retired for a year and moved to Denmark, coming back with a different repertoire. His career waned and waxed. I once commented in sleeve notes when Hot Vultures recorded his Taking My Time, a veritable paean to procrastination, that if the song illustrated his philosopy of life, it probably explained why his musical career showed a marked degree of inertia for many years! But he’s always been a hero.

Red House Records eventually recorded a series of fine albums with him like 1996’s Stargeezer, plus the appropriately titled Legends Of Folk shared with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Utah Phillips as well as reissuing the three KR&G albums. Somewhere in there he had a triple bypass heart operation (rumours were that long-time fan Bonnie Raitt helped out with the bills) and came back good and strong. KR&G re-formed but eventually Dave Ray passed away. We kept in touch, even though his last proper UK tour was in 1981 when he excelled at Cambridge Folk Festival.

“Well, I was born in ’38 and brought up in Rochester, New York, except for two years during World War II when I was a kid. Lived in Oakridge, Tennessee for a couple of years. Just grew up normally in Rochester, went to high school there. I was good at science and mathematics and I had an interest in flying and airplanes at the time – used to be a model airplane builder, so by virtue of all that I went to the University of Minnesota as an aeronautical engineering student. That was 1956.”

“That was the beginning of it. There was a small scene going on at the time where once a month or something like that a bunch of people would get together with banjos and guitars, sing songs. There was some kind of a political bent to some of it, but most of it was just people interested in traditional music.”

Koerner had no idea that what he was getting involved in was the start of a national phenomenon that would sweep the States and eventually the Western world. “At the time, it was just something that happened and I didn’t have any idea what was coming along. I was starting to learn about it and learning more and more songs so that I could perform a little bit. The first job I had was about six months after I started, at a fraternity party. I played a few folk songs. And some girls were there who had to give a dance thing and they wanted some folk music for that to accompany them, so I did that. And then I was in it, you know.”

“And somehow that was the beginning of the end of the school. It was very shortly after that I started hanging out with this guy, and one day I just quit school, took what money I had, we got in his car, we drove to Florida and through New Orleans over to Los Angeles. This was the first time I was out on my own and I didn’t know what to do with myself. I got kind of lost at it and I joined the United States Marine Corps – something I still marvel at that I ever did. I went through the boot camp out there in San Diego, and then up to infantry training regiment. Then a couple of things happened. I’d been there about a week and I got in a car accident, which was fairly serious, and that put me in the hospital for a while. While I was there it was the first time I had a chance to think. I started thinking about just getting out! So I used a few methods, and in another few months I managed to get free of the military. Also, while I was there waiting for that to happen, there was a Playboy magazine which had an article about this new phenomenon, the folk music coffee houses, including some of them up in Los Angeles, so I went up to check those out and that was quite interesting. People were performing and they were getting good audiences.”

“I’d heard some blues which I thought were kind of interesting. Josh White was one. It was kind of slick, but it gave me the feeling of what that was all about. Dave Ray was into it, and I started getting into it largely by virtue of hanging out with him. I can’t remember exactly how I met Tony Glover. Actually, I went back to Rochester, New York, for a while, and I used to go down the Village in New York City, and started getting interested in that scene. Dave eventually wound up living there for a while, and on one of those trips to visit Dave, that’s how I met Tony, and that kinda made all that more solid. They were into getting the old recordings, as best they could, and finding obscure stuff, and then that became my bag, along with them. And we proceeded for a couple of years at that. You know, there were people on the East Coast and West Coast doing blues, but they were not jumping into it head first and just going for it, and somehow we wound up doing that, and tried to sort of live the life, in a sense.”

“Dave was out there avoiding going to college and working in the garment district. He had a job being a professional beatnik for a while. He’d sit in the window of a coffee house with a beret on and read, so they’d have some atmosphere when the tour buses came round.”

“There was this one coffee house that was like an old house that was converted – not very much converted – and it didn’t have no sign on, you had to know it was there. Dave and I played Friday and Saturday nights, and Tony played Thursday and Sunday, something like that…A lot of the playing got done at after-hours parties. That’s when we really got together. We were hanging out and developing this more or less together. There was a couple of guys who had a magazine call the Little Sandy Review and they were interested in what we were doing and gave us some nice reviews. They also got us in contact with the record company that made the first record, out in Milwaukee. That’s Audiophile Records.”

Blues, Rags & Hollers came out on the tiny Audiophile label in the summer of 1963. A few gigs and several hundred sales later, it came to the attention of Elektra’s Jac Holzman, who promptly bought the masters and re-issued it, shorn of four tracks to bring it down to a length where a better vinyl pressing quality could be achieved. These were finally re-instated on the Red House CD re-issue, which also has lengthy and fascinating notes by Tony Glover about the local scene at the time and the events surrounding the recording. Meanwhile, as Glover told me in 1995, word was spreading…

Koerner suggests they had an easy ride. “We followed, I think, the closing set of the regular concert which was Theodore Bikel who did like a three-day set in Serbo-Croatian. Anything that had a rhythm to it would have woken people up, and we definitely had a lot of rhythm. Kweskin’s Jug Band was also on the same show, I remember that. Us and the Kweskins were kinda like the young Turks. Everybody else was getting kinda serious about traditional folk music and we were out there having a good time and saying ‘what the hell?’.”

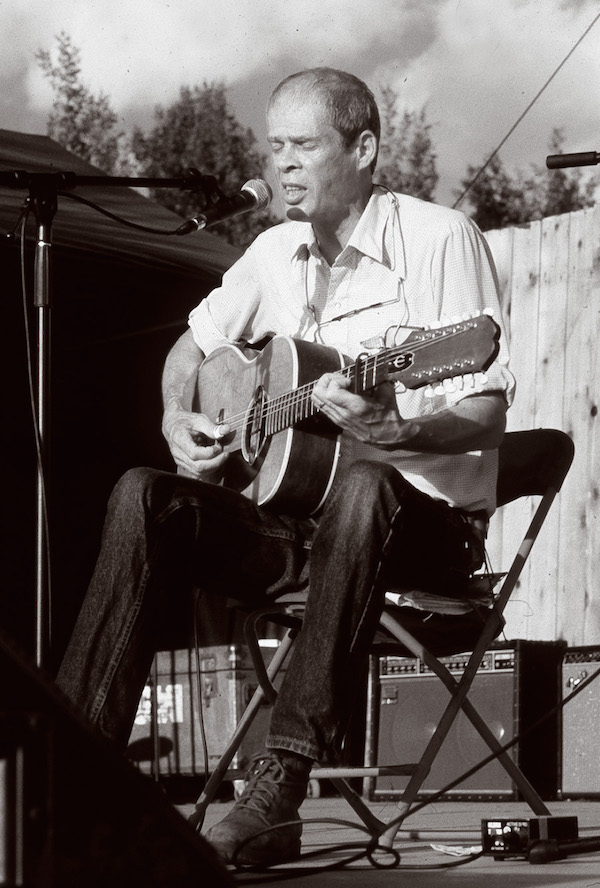

In September 2009, four and a half decades after I first met him as a teenage fan, we had the pleasure of hosting the now 71-year-old Koerner for a gig at the Green Note as he briefly passed through London after an Irish trip. The sold-out audience thrilled as he wheeled and stomped his way through a set of great American folk standards, the sort of songs ingrained into the consciousness of folkpersons of a certain age but hardly anybody sings any more – Acres Of Clams, Wabash Cannonball, The Days Of 49, St James Infirmary, Danville Girl – all in his completely original, funkily syncopated style, those long spider legs still spilling out to meet those rhythmic boots.

The following day John and I sat in the fRoots kitchen and continued the conversation about his early days, philosophy, influences and general guitar player bollocks. I started by recalling Bob Dylan’s reference to him in his book Chronicles, talking about his young days in Minneapolis, running into John Koerner in a club. “With my newly learned repertoire, I… dropped into the Ten O’Clock Scholar, a Beat coffeehouse,” wrote Bob, “I was looking for players with kindred spirits. The first guy I met in Minneapolis like me was sitting around in there. It was John Koerner and he also had an acoustic guitar with him. Koerner was tall and thin with a look of perpetual amusement on his face. We hit it off right away. When he spoke he was soft spoken, but when he sang he became a field holler shouter. Koerner was an exciting singer, and we began playing a lot together. I learned a lot of songs off Koerner …”

“Well, I’ve read the book,” says John, “and sometimes what I see is either he’s got a better memory than I have or he’s making stuff up. It could be either way. Because some of that I don’t remember all that well, but it doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. But the general sense of it is correct.”

“I think that was something that was happening all over, but that’s the first I came across it. It was starting to happen everywhere and Minneapolis… Minneapolis is an interesting town. People definitely got their own style there and they don’t need to be from the East Coast or the West Coast, they don’t give a shit about either one of those, they’re part of their own style. So there was that scene going on and Dave Ray was part of it and Dylan… everybody knew that he was Zimmerman, but he was calling himself Dylan, so then you had your choices about what you wanted to call him.”

“So that scene was going on there. Also there was the guy who started me out on playing guitar. One day I was an engineer, the next day I was beginning to do the other thing. Harry Weber was the guy that first got me interested in the music. He played a six-string guitar and did folk music.”

“Actually at some point there was a bunch of people who would get together on some nights, banjo players, guitar players and all that, and what was going around was bits of traditional folk stuff. That’s kind of what he played.”

The first of the old blues guys that Koerner encountered personally was Big Joe Williams, a rough old travelling country bluesman from Tennessee, famous for his song Baby Please Don’t Go – later covered by everybody – and his ramshackle nine-string guitar.

“We used to hang out with Big Joe. This guy had a coffee house, actually had a couple of ’em, but he somehow brought Big Joe to Minneapolis. He was something else, I tell ya. He had that nine-string. And it was put together so crudely you couldn’t believe it. And I just realised at that point that if you want to screw round your guitar and change it, it’s easy. It was definitely ‘Oh, OK, you can do that’.”

Was Jesse Fuller – one-man band and composer of era standard San Francisco Bay Blues – ever around?

“Sure. Around 1960 I got on a motorcycle with Red Nelson in Minneapolis, and we drove all the way to L.A. and later on up to San Francisco – somehow I had a job playing the Troubadour or some place up there – along with Jesse Fuller. They called him Jesse ‘Lone Cat’ Fuller, you know, and boy, he lived up to it! He stayed in the club. He laid out a sleeping bag on the stage, and I think he had a radio or television, or something like that, and that was it. And we were all really drunk, and screwing around with fire extinguishers and all that shit, and he came and said ‘You boys get the hell out of here, I’m trying to sleep!’ He was one of the good ones, that’s for sure.”

So Big Joe inspired John Koerner to start experimenting with extra strings on his guitar. What did he try first?

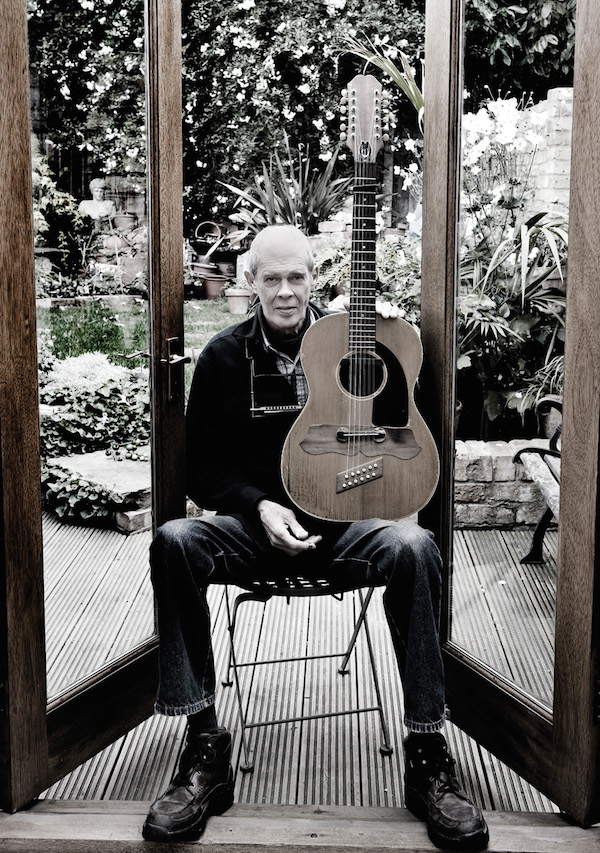

“I can’t remember the first time I put an extra string on. One of the earliest guitars I had was a [Gibson] Army & Navy, and I think I just had that as a six-string, although maybe at some point I modified it, but that was the beginning. That was just a nice old, well-made guitar, nothing fancy, that worked out fine. I don’t remember when I first started to change strings on guitars, but at a fairly early point I got into fooling around with instruments. I bought a twelve-string and it was all messed up, and I put a new top on, because I’m handy, and yeah, I went through a number of guitars that way.”

“At one time, I think it was that Army & Navy special got stolen. I went down to Johnson City, Tennessee, and I needed a guitar and I went to a hock shop there and they had this really bad guitar for $15, and here’s a clue, I wanted to turn it into a seven-string and I did it right in the shop. I hadn’t even given the guy the money. He thought ‘What’s going on here?’, you know. I went right down the street and got a drill bit or something like that so I could make a hole, put a peg and changed it all around and played him a couple of songs. But that indicates that the previous guitar must have been that way.”

“I did try other arrangements. I had an eight-string at one point. I can’t remember what that was all about. And at one point I strung one up to be like a tiple – so you got two pairs and two triples.”

“That would have to be a nine-string at that point. I don’t quite remember where that came from. See I’ve had two of ’em, this was a Gretsch model 75 or something like that. I played that for quite a while. That’s the one that I gave away when I quit music.”

Pardon?

“This was winter 1972, I was going through what everyone would call life-change thinking kind of stuff, and I decided to give up music forever. I played a job in Jack’s Bar, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and I was going to sell it at the end of the job, and this guy came up and was going to give me $200, and I thought ‘Oh, hey, go the whole way’ and I just gave it to him, ‘Forget it’, with the case and a bunch of other stuff in the case.”

“And then I went to Denmark to live, I lived there for three or four years. I was a waiter in a bar for a while. I worked in a porcelain factory for a while. I was a slomper in a big department store, the guy that cleans up in the morning. When you get down to the bottom that’s what you do. It ain’t bad. I liked cleaning up.”

Enter another Gretsch …

“So I played that for a while. And it was OK, but it was a little awkward for me somehow. At some point I went back to this one I’m playing now, the Epiphone, that I bought somewhere around 1977.”

And finally his old given-away model 75 came back home…

“I had a job a couple of years ago, near Boise, Idaho. And I was just getting ready to go on the stage and this guy comes up to me. He says ‘I’d like to introduce you to an old friend of yours’ and I’m thinking ‘Oh, who the hell is that?’ and we went out in the parking lot and he had a pickup, and in the back of the pickup, well, there it was, just like it was. And it still smelled the same, for God’s sake! Yeah, that was totally amazing. I’ve taken a look at it and I can see that I didn’t do a very good job of spacing the strings, so I’m gonna redo that, but at some point I will put it back exactly the way it was before.”

The first Blues, Rags & Hollers LP was made for the small Audiophile label, before being licensed to Elektra nationally. “When our record was made we sent some of them off to Elektra Records and they picked up on it and reproduced the record. They also had us come out to New York City to record a second album, and on that visit they also managed to slip us in as a late thing at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, so now we had records and we were presented to a wide audience, and at that point it got to be kind of easy. There was people wanted to manage us and all that stuff. Betsy Siggins from the Club 47 was there and got us to play up there. I remember we went up there to play and it was totally amazing to us. There was a line halfway round the block, holy moley! So at that point it wasn’t hard to get jobs.”

That Boston/ Cambridge area became his second home …

“Yeah. I jumped in on the scene there. It was kind of a wild scene. I’m not sure what some of those people thought of me, but I lived with some of them over a period of time. That’d be ’63, ’64. I quite enjoyed it. When I think back on it, it was too much, you know. It was a lot of drunkenness, running around playing, doing this and that, it was kinda nuts, but that’s the way things were at that time, in general.”

The impression one got from Jim Rooney & Eric Von Schmidt’s book about that scene, Baby Let Me Follow You Down, was that there was a party in somebody’s apartment every night with half the musicians you’ve ever heard of playing there. “Yeah, it was kinda like that. That book is a little weird in one way. It’s a bit of a soap opera that they’re talking about – a lot of personal relationships, all that kind of stuff. Not that it was inaccurate, by any means. Yeah, it was quite a scene. I had my own part of it, on my own, but also hanging out with those guys.”

So what got him to England? I used to read the weekly music papers and I remember quite vividly that one of them – possibly Record Mirror or New Musical Express – had a column where they asked the Beatles what their favourite records were and John Lennon said Koerner, Ray & Glover. “Fucking hell, the Beatles have heard of these guys!” I had no idea that anybody so famous could have heard of something that obscure which I was listening to. “Me neither,” chuckles Koerner.

What does he remember about his first visits to the UK?

“There was a guy, and I can’t remember his name, possibly associated with a place called Cecil something…?”

Cecil Sharp House – Roy Guest?

“That’s it. Somehow, and I don’t know how, I got hooked up with him, maybe through Manny [Greenhill, of US agents Folklore Productions]. I remember coming here – and I’d never been out of America before, the big US of A – and I remember my plan was – actually I didn’t have any plan really, but it was to get a taxi and have him take me to some hotel, right?”

“And I’m on a bus from the airport into town and I’m looking for taxis, and I couldn’t see any taxis. No taxis! Well I was looking for something completely different. I saw all these wonderful cars running on diesel, but I didn’t know what they were. And finally I figured it out, and he took me down to Russell Square and I went into a bed and breakfast, it was three quid a night. It was great.” Koerner was soon to be found playing regularly in the hottest folk venues of the day like Soho’s Les Cousins in Greek Street. “Oh yeah, I played there a bunch of times. It seems to me there was a couple of famous people showed up down there. And I remember playing that damn all-nighter a couple of times. Glad I don’t have to do that again! I remember the guy that ran the place, there was a son…”

Andy Matthews.

“I remember that guy, we were outside of the place one time talking about running – racing. And I thought, well I can beat him – he’s a big, fat guy, you know. Obviously I can beat him. So I don’t know if we made a wager or what. It was just to go a block. That little sucker he just took off on me! He couldn’t go long, I don’t think, but for the distance he just went.”

“I remember Mox [Gowland], I remember Les Bridger, I remember Paul Rowan, and outside of that I don’t remember much. I remember those funky people I used to hang out with as opposed to the rest of it. I think Gill Cook [manager of Collett’s Folk Shop] helped me out with a place to stay at least part of the time. It’s kind of a blur in a way, but what I do remember is that I was around here long enough to be used to the buses and the Tube and have my own local that I kinda liked, and felt at home here.”

Back when he started out he was doing blues, and pretty soon he was doing his own bipity bopity version, writing his own songs rather than doing covers. Did that just happen naturally? Was there any great thought behind it?

“Well, there was a point at which I realised that when you listen to all these blues guys, each got their own thing. They make their own songs and the way to be like ’em is not to copy ’em but to go through the same process. So I started to try to make up songs. Good Time Charlie was one of the first attempts at that. And also you gotta turn yourself loose on style. There’s no problem with copying somebody for a while just to see what’s going on, but eventually you’ve got to let yourself do whatever you come up with. People call me an original. I guess that’s true. I didn’t try to be an original exactly, I just did what I could.”

“I didn’t really stop listening to others, but the process is more like what you can steal in, some little lick. And that got to be eventually broadened. I remember somewhere in the late ’70s I got interested in shortwave radio. It used to be interesting back then, now it’s changed because of the internet, but I remember listening to Radio Cairo, and some interesting music. They’d do the call to prayer. I heard that and thought ‘Oh, there’s something interesting there’. I don’t know how I integrated it, but there was some way in which a little piece of that got into how I sing. And whatever. You hear something interesting, and if it seems to fit, take it.”

And so, as we heard, he gave up music forever, and a year later decided it was alright after all, but didn’t want to play the stuff he was playing earlier any more. He’d previously told me that he didn’t really like the lyrics that he’d done before…

“Well, alright. There were a number of things involved, of course. I don’t know, maybe I grew up a little bit in that time. One thing, it started seeming odd to me at that time to try and be like a black guy, which is sort of what we did back then.”

“And also I came across the folk music, one of Lomax’s collections in the house and looking over thatmaterial I realised how good it was, really solid stuff, good poetry and good imagery. And I thought, well OK, I’ll try and do that, see what happens. And I’ve never regretted it.”

On his ’60s records, Koerner was an incredibly manic, crazy, flash guitar player. To this day, people still say ‘How did he do that?’ – and that even includes fans like Martin Simpson. Had he also decided that he didn’t want to go down that route any more, to simplify things?

“Sort of. Yeah. Of course it’s a process. It took some time to feel my way through it. I wanted to sing the song. I became more interested in the singing of the song than the guitar, and I wanted to make the guitar work simple enough so I didn’t have to think too much about that. And like I say, this was a process of some years that that happened over. But I know what you’re talking about. Paul Geremia thinks of Spider Blues as being one of my best records, because he says I was on the top of my form with my guitar playing. But on the other hand, this record drives me nuts. It’s all that ‘My baby’ this and ‘My baby’s legs’ and I don’t know what the hell all those things were, you know, and when I look back at it, it feels a little adolescent.”

“Well, sure, at the time. I wouldn’t try to duplicate it now, or even try to do the same thing any more. But I understand all that. It’s just my own feelings about some of those things are – with some distance now, looking back on it – it seems a little weird. But I understand why other people are interested in it.”

As a Koerner completist, I’d bought a single of his that seems to have only come out on British Elektra, in 1966 (EKSN 45005, for you trainspotters). The two sides, Won’t You Give Me Some Love and Don’t Stop never appeared on an album. When I’d met him in 1995, Tony Glover, the unofficial KR&G archivist had been stopped in his tracks by this revelation.

“Do you have that? I’ve been trying to find that fucker for years. I remember that session! It was a single,” explains Glover. “The idea was that there was a lot of folk rock stuff round – ‘let’s try Koerner with a band’. There was Al Kooper and Felix Pappalardi. I was playing harp, I think there was a drummer from the Blues Project. I had a fever of about 103. People said ‘whatever happened to that session?’.

I theorise that it might have something to do with Joe Boyd, who was running the UK end of Elektra at the time, but when I later enquire from Joe he has no recollection of it whatsoever. But then I once saw Koerner at the legendary London underground club which Joe ran called UFO, and he doesn’t remember that either. It’s all a mystery.

So he moved to the great discarded American folk song repertoire – all those classic ones which were in the song books of the era but nobody actually sang any more – Acres Of Clams, Careless Love, Abdullah Bulbul Amir …

“I was in Denmark. I got Henrik Pedersen and a guy named Jørgen Lang, he was a harmonica player, and Henrik – I don’t know whether he’d been doing it before or not – he decided to play the washboard. And we played all over Denmark. Started out just going into open stage kind of things, just to test it all out. Then at a point I decided I’d go back to the States and try and make a little money for a couple of months. It kinda worked out. I quit my job at the porcelain factory. I went over and I had these jobs, well, OK ‘Spider John Koerner’s gonna play’, right? And I get up there, and I remember the first job I played, I played this set, all these folk songs, and then I played another set of all folk songs. Took a break and some of the people came up to me and asked ‘What the hell are you doing?’ And it was like, alright, this is going to take some getting used to! But eventually, like I say, it came around and that’s what I felt like doing.”

“I had the books and my own way of playing, and just put the two together. It’s not that difficult, and like I say, the material is really tasty stuff, and if you’ve got a little style to play it with… and, you know, the ones I play are the ones that were in the popular collections, so why not? Actually I have to admit I do get a kick out of that, taking these songs that some of those people wouldn’t play any more …”

“My attitude is ‘You guys abandoned the ship. I’m gonna show you how to play them, and how people like them when you play that way.’ I played a job with Dave and Tony down in Chicago, and the New Lost City Ramblers were on the same bill. They played The Cuckoo, I think they were in front of us. And me and Dave played that, he was into his jazz style, and I said ‘OK, now we’re going to go out and show those boys how to play Cuckoo’. A little arrogance there, but you can take those songs if you know how to treat ’em properly. You have to have some sense of what they’re supposed to feel like, but you can do that, man, they’re just solid.”

“If I’m in good form the whole idea is to feel that song as it’s going along as though you are part of it. I don’t pick songs to play unless I know how to relate to them internally. I rejected plenty of songs because I just couldn’t do that. So the object, every time, is always to try and feel that story as you do it.”

He could join America’s hordes of singer/songwriters and start making really boring songs about it, but that probably wouldn’t do much good either! “Actually, I was thinking one time of – do you remember flagpole sitters? That was way, way, way back. People used to do that, and I thought ‘Yeah, that hasn’t been done for a while’. Maybe I should go up on a flagpole and broadcast and talk to people on the phone and try and get the message out. They’d send a camera up there to get a look at you, wouldn’t they? I’m just joking of course …”

“The main thing you want is for your venues to be places where the people who are going to come there are looking forward to it. Sometimes you play jobs and you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, or something like that. You want the public to be there and enjoy it, you want the boss to feel like he’s made good business and you want the performer to go away with some wages that are reasonable, and that’s it, that’s showbiz.”

Shop

You can buy CDs and downloads at our online shop.

Writing

Technology (2002)

Photographers (2002)

English Country Dance Music (2003)

Is That All There Is? (2005)

Self Worth (2007)

Television (2008)

Musical Racism (2008)

Small Venues & the Folkistanis (2009)

Existential Stuff Crisis (2013)

Festival Challenge (2014)